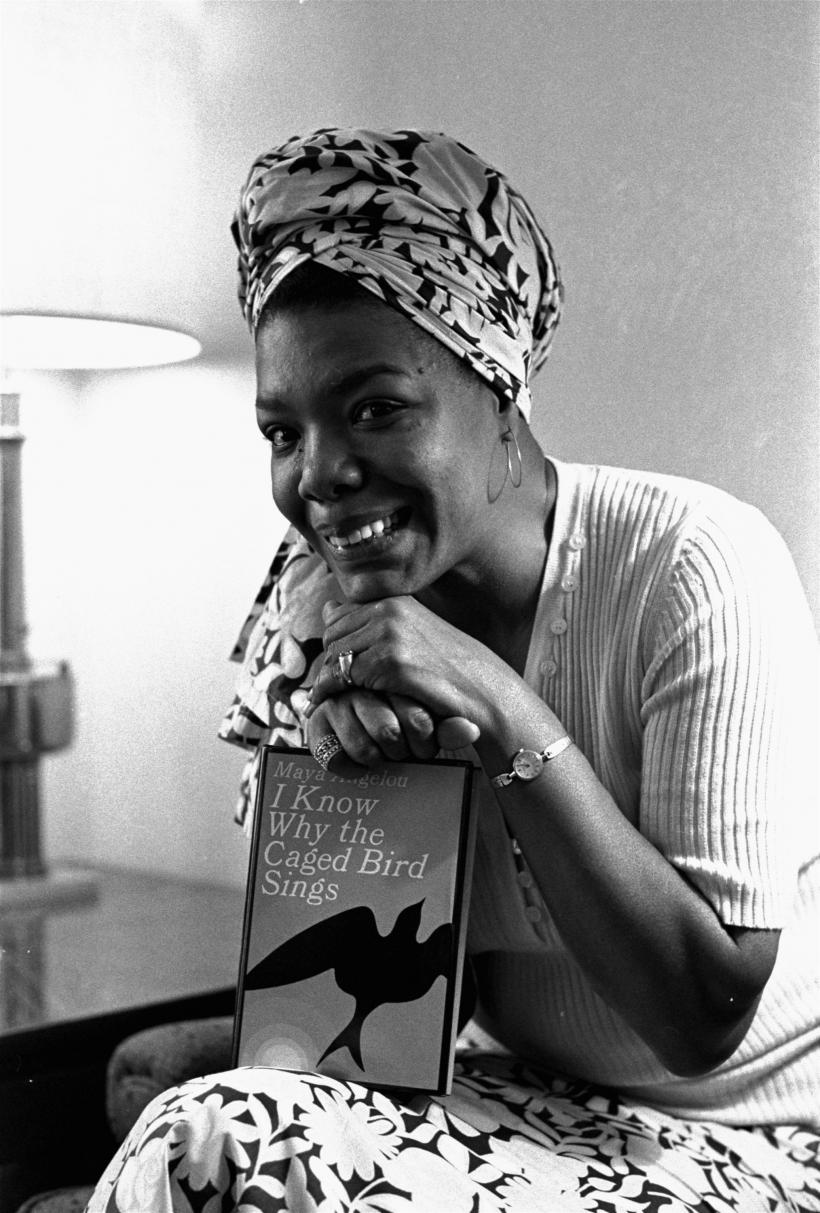

Maya Angelou's life and writings are a national treasure. (Photo: November 3, 1971 Credit: © WF/AP/Corbis)

As Americans struggle to deal with the divisiveness and polarity within our country, the presentation of the documentary Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise (February 21 on PBS) is a welcome respite. Through the use of archival footage and interviews with Angelou — and commentary from those who knew her — a portrait of her fierce courage and individuality is drawn. Angelou’s dedication to speaking her truth stands as an example of her personal integrity.

In a life spanning eighty-six years (1928-2014), Angelo witnessed and was impacted by the Jim Crow mindset of the 20th century South.

Angelou’s parents, a World War I veteran and a “bright and courageous woman,” sent her and her brother Bailey to live with their paternal grandmother after the breakup of their marriage. The separation left Angelou with tremendous loss and feelings of rejection. However, a protective Bailey and Grandmother Henderson (a child of former slaves), were solid presences in her life. Her grandmother owned both a local store and property in Stamps, Arkansas. The extended family household included a disabled uncle.

Angelou relates stories of life in Stamps that are hair-raising. “I was terribly hurt in this town,” she recounts. Angelou describes the “loathing” with which white people would look at her. She also vividly depicts the imagery of horse-mounted Klu Klux Klansmen, as they appeared over the hill, riding toward her house. They would hide her uncle in the potato bin — covered with wood slats, spuds, and onions.

The “pain of growing up as a black girl in the South” would give form to much of Angelou’s narratives. “When I reached for the pen to write, I have to scrape it against those scars,” she said. It was her vivid use of language to express intense personal anguish that resonated so deeply with others.

The pivotal experience that shaped Angelou’s life occurred when she and her brother went back to live with their mother in St. Louis. At the age of seven, her mother’s boyfriend raped her. She told her brother about the incident, and the boyfriend went briefly to jail. Soon after, he was found kicked to death. Angelou recalls, “I had to stop talking. I knew my voice could kill people.”

Her mother returned the children to Stamps. Angelou began to heal under the watchful eye and nurturing care of the grandmother who always believed in her.

During the next five years, Angelou went mute. She also read everything she could get her hands on, memorizing texts, including Shakespeare. Angelou notes, “When I decided to speak, I had a lot to say.”

At sixteen, while living in San Francisco, Angelou had a sexual encounter. She became pregnant with her son, Gary Johnson. Featured in the movie, Johnson attests to the strong bond between himself and his mother. He tells a riveting story about his mother’s fearlessness during a frightening civil rights demonstration.

“My mother taught me a love of justice,” says Johnson. “A love of doing what’s right. If you really have something to protest, you should be on the streets.”

Supporting herself and her child through her artistic abilities, Angelou worked in nightclubs as a dancer and then as a singer. A striking figure at six feet tall, Angelou developed a repertoire of Afro-Caribbean music and became known as “Miss Calypso.” Performing with a dance company in Las Vegas in the 1950s, Angelou describes how top black talent, like Lena Horne and Sammy Davis, were unable to leave their rooms or use the hotel facilities where they headlined.

Angelou spoke of putting the tradition of the “slave narrative” out to the public, writing “I…but meaning we.” It became a touchstone for readers of all backgrounds.

When Angelou auditioned to be a dancer in the San Francisco production of Porgy and Bess, it led to a worldwide touring opportunity. It enabled her to travel extensively. While in Paris, she met James Baldwin, who became a close friend. The richness of these experiences was always in conflict with the guilt she felt about leaving her son.

Returning to America, Angelou became acquainted with Langston Hughes. He encouraged her to become part of the Harlem Writers Guild. She immersed herself in the fertile environment of the arts and culture. In 1961, Angelou performed in The Blacks, the groundbreaking play by Jean Genet. The cast included actors James Earl Jones and Cicely Tyson.

Angelou’s life revolved not only around her creative endeavors. She maintained a strong political and activist sensibility. After hearing Dr. Martin Luther King speak at the Riverside Church on non-violence, Angelou became a coordinator for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), in the New York office. She met leaders in the African liberation movement. A relationship with Vusumzi Make, a South African lawyer and activist, took her to Cairo. She then went on, alone, to Ghana.

When Malcolm X made a pilgrimage to Africa, Angelou connected with him when he visited Ghana. She joined him in his efforts to have the United Nations condemn America for racism. When speaking of how she was “shattered” by his assassination, Angelou states, “I loved him so much.” That same year, King was murdered — on the day of her birthday. The grief was overwhelming.

As Angelou came out of her mourning, she began to share her personal stories with others. She was recommended to a publisher, after recounting personal tales at a party she attended with Baldwin.

Challenged to put her oral histories to paper, she created I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. Published in 1969, it was a new type of writing. Open and frank about the experience of being black — as well as about her childhood rape — it was a primary example of ‘personal identity” prose. Angelou spoke of putting the tradition of the “slave narrative” out to the public, writing “I…but meaning we.” It became a touchstone for readers of all backgrounds. Oprah Winfrey, in her interview, defines her revelation: “Somebody knows who I am.”

Angelou had many relationships and several marriages. One of her husbands, Paul du Feu observed, “There wasn’t room beyond the written word.”

A dancer, singer, actress, poet, writer, and lecturer ⎯ Angelou was larger than life. There were no boundaries to her talents. She worked with musicians, including B.B. King. She played the grandmother of Kunta Kinte in the 1977 version of Roots. She directed the film Down in the Delta, about a mother sending her daughter away from Chicago and back to Mississippi, the home of previous generations.

Angelou frequently spoke to the female African American experience. “Black women are the last on the totem pole,” she said.

However, her message was universal. It was the directive to believe in your own voice, and to know that you are enough.

“We may encounter many defeats, but we must not be defeated,” Angelou pronounced.

One of the high points of Angelou’s career was the delivery of her poem, “On the Pulse of Morning,” at Bill Clinton’s 1993 inauguration. One of its stanzas is now poignantly relevant:

Lift up your hearts

Each new hour holds new chances

For a new beginning.

Do not be wedded forever

To fear, yoked eternally

To brutishness.

Her voice remains indelible.