When I read, I imagined the characters gathered together in that backyard.

Long Reads is a bimonthly feature, showcasing long-form essays.

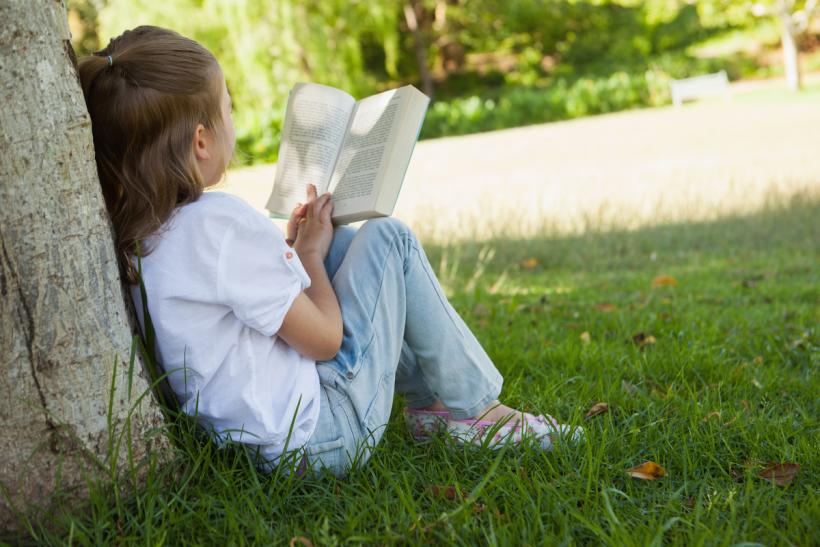

When you’re an obsessive child, nothing prevents you from sharing your hobbies. Your mother will say seriously, stop reading, I have to go pee, and then you’ll follow her into the bathroom and lean on the jacuzzi tub, fingers wedged inside a hardcover, waiting.

This is how I read 4,224 pages aloud to my mother over the span of seven years, and while she listened — first, 35 and energized; later, 42 and overworked — my readings remained largely the same. I had a neurological speech impediment, a stutter. I had carried it since birth.

I began reading to my mother in 2000, the year our neighbors believed the apocalypse would occur. On New Year’s Eve, 1999, they stockpiled food and water and buried cash in coffee cans underground. Everyone feared the millennial year would set our computers back to zero.

But my mother never seemed concerned. It was my stutter that worried her the most.

***

Our Old House held a mysterious sort of magic. We lived there the first ten years of my life, in a one-story brick home approaching its one-hundredth birthday. The acreage was generous, allowing my mother’s flower garden to expand into rows of towering monkshood and grassy knobs of spiderwort. One year, my parents commissioned a tall treehouse, and it became my lair. On weekends my mom would climb the treehouse ladder, and we’d mash wet leaves, rainwater, and spider legs into cups and call them potions. We’d cackle, pretending to drink the mixture, claiming we instantly had magic powers.

But the Old House had another magic, the kind that kept us up at night.

It was built in 1907 and was the first house on the block, the residential nucleus of the neighborhood. For decades, it was rumored to be haunted. In the 70s, one of my mother’s friends would ride her bike around our future neighborhood, passing the elementary school and the local grocery store. But she always pedaled quickly past our house.

“A man died there,” she told my mother, just years ago, not realizing we had lived there. “He committed suicide.”

My mom doesn’t believe the suicide happened, mostly because we haven’t found confirmation online. But she does believe the house has secrets.

Once she woke in her bedroom late at night, my sister was calling out her name. After her eyes had adjusted to the dark, she saw my sister standing in front of the fireplace. That was another quirk of the old architecture — there were multiple fireplaces throughout the house, mostly oak, with dark and dusty hearths. My sister was standing in front of my parents’ fireplace, a four-year-old in a nightgown. And there was a woman behind her, skin transparent and blue. She was wearing a skirt, my mother remembers. And she had her hand on my sister’s shoulder.

My mom cried out, waking my father next to her. But the apparition was gone by the time he grabbed his glasses.

The original, twentieth-century hardwood flooring remains in three places: the foyer, the dining room, and my old bedroom. Each night, I’d close my eyes and hear the creaking, the shifting of the wood. On nights when I was brave enough, I took tiny peeks into the darkness. Several times I saw the lamp on my dresser shift and curl, come alive. Once I saw black masses in the corner, billowy and ghoulish.

Our next house was newly built, two-stories, and in a nicer subdivision. I hated it, of course. While I didn’t miss the creaks and shadows, or the nights of inadequate sleep — I did miss the sense of history, of familiarity.

My first home became a monument to which I explained my life: the sunny swell of curtains, the adrenaline of mystery, the floors that seemed to creak in joy and solitude.

And the outside — the garden and the oaks and the treehouse— became the place my mind was always resting. When I read, I imagined the characters gathered together in that backyard. When I daydreamed, my wedding was held just a few feet from my old treehouse. If my thoughts were combed through, polished, comprised into a play, then the outside of the Old House would be the only stage.

Ten years after we sold the Old House, the new owner tracked us down and left a message on our answering machine. She said someone — or something — had been calling out a name. For days and weeks, there was a voice, and there was a name. Did the name mean anything to us? “No,” my dad said dismissively, forgetting the name as soon as she said it. “Doesn’t ring any bells.”

It is only now that I see how my views of the unexplained, of the otherworldly, were shaped by those years — by that house. My mother is a dancer, a painter, and cook. My father, though pragmatic, is the type to sit alone around a campfire, mesmerized by the flames. Perhaps I was predisposed to seek out a world more illustrious than our own.

What she doesn’t say — but what we’re both thinking — is that my mind had no other entrance at the time. If she didn’t meet with me in the clouds, in imagination and storybooks, she wouldn’t have heard my voice at all.

But I was a little girl with a stutter, a disability that could not be fixed or explained. And it was because of that speech impediment that I left the world of spoken words and started a conversation in my imagination, one my stutter couldn’t prevent.

***

At age eight, I had stuttered my entire life. The speech therapist at my public elementary school kept a chart on me. I imagine it included the word chronic. I was unaware of how serious this was. It would take middle school, with its class presentations and subsequent teasing, for the social consequences of being different to take effect fully.

In my Girl Scout troop many girls were homeschooled, Christian, and read historical fiction — all of which I found boring. So I turned to the kids at my public elementary school, imagining some form of Scholastic book club. It was then that I learned something crucial. In the third grade social system, reading wasn’t cool.

Don’t you all see how fun this is? I wanted to cry out.

Instead, I whispered, “Yeah, b-b-books are weird,” and hid Junie B. Jones in my backpack. My classmates treated books the way I sometimes treated Girl Scout girls: with cold, eight-year-old contempt.

I was distraught.

Weeks later, I noticed The Sorcerer’s Stone on my sister’s dresser, underneath a bottle of perfume I had been spraying for fun. For whatever reason, I opened to the first chapter and couldn’t seem to stop. I read the first Harry Potter book in a handful of days and found the next one at my school library.

In the second installment, and at only 12-years-old, Harry becomes an outcast because he can speak another language. Not just another language, though — one that others misunderstand and see as different, even dangerous. I began to imagine Harry and I having conversations about this, accepting how the words on our lips somehow made us special.

I was eager to convince everyone I knew to read the series. But at the time, the only person I could convince was my mother — and that took two years. She claimed to have no time to read it herself, which was probably true. It seemed she only agreed because I followed her around the house, asking and asking and asking. (As a child, I had a particular type of enthusiasm that was perceived as annoying.)

Thankfully my persistence paid off. My mother didn’t have time to read the books herself, she said, but I could read them to her.

By the fall of 2000, there were four novels published. The books had gathered a following even in our small Tennessee hometown, comprised of 12 square miles and 50 churches. At the time, our only abstract art was a set of dark maroon, metal poles — the tallest one holding a rusty gray tractor. We called it the Tractor on the Pole. This pole-and-tractor combo is still positioned beside a red tobacco barn, on the line where Tennessee meets Kentucky. Locals from both states use it as a landmark. (“Where’s the picnic at?” someone might ask. “It ain’t far — just past the Tractor on the Pole.”)

But while everyone in my hometown had heard of the series, few condoned reading it. Most people were well intentioned but misinformed, believing the books taught children witchcraft. My mother laughed at the idea.

“Who are the villains in Disney cartoons?” she’d ask, putting on a layer of lipstick in the mirror. “You know, the cartoons everyone loves.”

I would think carefully, then say, “W-w-w-witches.”

She’d nod, picking up the Virginia Slim she’d left lying in the ashtray. “Exactly,” she’d say, inhaling slowly from her cigarette, and though I didn’t yet grasp concepts like hypocrisy, I would nod all the same.

It was decided. I would read the Harry Potter series aloud to my mother.

***

The process was slow. I dreaded each paragraph of description, each long, winding sentence. I’d stutter hard, sometimes gutturally, gasping for air, like I was reading underwater. I grew to dislike multisyllabic adverbs, like abruptly or inquisitively, which J.K. Rowling often used to describe the dialogue.

But oh, the dialogue. It was here that the repetitions, the prolongations, finally seemed to dissipate.

“'THERE IS NO HARRY POTTER HERE,'" I would roar, impersonating Harry’s hostile, no-good uncle. “'I DONT KNOW WHAT SCHOOL YOU’RE TALKING ABOUT! NEVER CONTACT ME AGAIN!’” I employed my deepest, angriest, British accent. “DON’T YOU COME NEAR MY FAMILY!’”

Glancing up from the page, I noticed my mother smiling in amusement. We fell into a fit of giggles, recounting my performance for weeks afterward. This was when I learned that an accent would mask my stutter, a tactic I began using with classmates (who were surprised that I could be funny).

But once the giggling stopped and it was time to continue reading, the stutter returned as it always had.

“‘And he threw the rrrrrrreceiver back onto the t-t-t-t-telephone as if dropping a p-p-p-p-p-p-p-p-p-ppoisonous spider,’” I read, disappointed, believing that the earlier moment of fluency was how I was supposed to speak, and everything else was just an embarrassment.

For the most part, though, I enjoyed our daily reading. My mother listened passively, often cooking or sewing while I read, not acknowledging my more disfluent sentences or my more fluent ones. She simply listened, and at the close of each chapter, would ask, “Well, aren’t you going to read another?”

I now suspect this reading was a therapeutic technique that she crafted, a hope of recovery as inspiring as Forrest Gump shedding his leg braces and outrunning the school bullies. Perhaps she thought speech was a muscle I could use enough, make strong enough, to reverse a diagnosis. I can’t blame her.

Our society is taught that disability is something you must cinematically overcome.

Later in life, I finally asked why she let her speech deficient child spend seven years reading a lengthy children’s fantasy series aloud. Her initial response was, “You just wore me down.” Which is fair. Personality traits aside, stutterers do know how to repeat themselves. But after a while, she found a deeper hypothesis. “It was a way for me to be a part of your life,” she said. “To see what excited your mind.”

What she doesn’t say — but what we’re both thinking — is that my mind had no other entrance at the time. If she didn’t meet with me in the clouds, in imagination and storybooks, she wouldn’t have heard my voice at all.

The doors of my mouth were locked shut.

***

With time, things began to change. I played clarinet in the middle school band and made friends who were equally involved in a fantasy world. Together we discussed Meg Cabot’s Mediator series and Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time. We watched The Lord of the Rings trilogy at nearly every sleepover. We loved Harry Potter the most, of course, and dissected the book-to-film adaptations with eager, enthusiastic analyses.

My inclination towards escapism had somehow won me friends.

By the summer of 2007, the last installation of Harry Potter was published, and I was 15-years-old. My new friends were in a punk rock band, quoted Ayn Rand religiously, and already had their driver's licenses. I was desperately forming my adult identity, on the cusp of change — both challenging and marvelous.

But I still had one last Harry Potter book to read. At 600 pages, the audiobook is over 21 hours long. As a person who stutters, reading it aloud took me months of daily reading. During the last sentence on the last page, I reached for my mother’s hand — something I hadn’t done in far too long. She looked up in surprise.

“‘The sssssscar had not pppppppained H-H-H-Harry for nnnnnineteen years,’” I read. “‘All was w-w-w-w-w-ell.’”

We cried — and blamed the book. But we both knew it was our grief, our closure of the seven-year search that had landed me here — intellectual and teenage and wild. And with a magic all my own.