Scientists Julia Shaw and Stephen Porter have gone ahead and confirmed every one of our goddamn fears. Their paper—"Constructing Rich False Memories of Committing Crime," recently published in Psychological Science—proves the chilling power of suggestion.

Shaw and Porter discovered that "certain tactics," dubbed "suggestive memory-retrieval techniques," are able to induce full-bodied, highly detailed and multi-sensory memories that never actually happened. The findings confirm the disconcerting notion of false confessions—not to mention the bastardization of what we like to call justice.

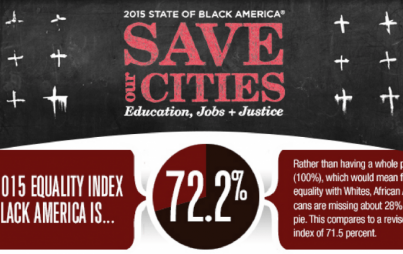

According to the Innocence Project, 25% of false convictions are attributable to faulty confession evidence, which has been procured with questionable interrogation strategies; exoneration is often only achieved with DNA testing, a practice that didn't begin until 1989. Complicating things further is that of the 258 exonerations in 37 states, 204 of them have been African American individuals, surfacing a not-so-subtle racial component in America's pursuit of justice. (Take this stomach-turning data, for example: 64% of the people who were wrongfully convicted of rape, and then exonerated through DNA, are black.)

The manipulation of memory is one salient means of wrongfully convicting American citizens.

"This assumption of memory as a largely reliable process traditionally forms a major part of the foundation of the legal system, in which memory accounts of witnesses—and when they confess, defendants—can play a key role in judicial decision making . . . indeed, a confession is one of the most potent forms of legal evidence."

This perceived reliability, however, is in fact highly dubious. Memory distortion and even sheer fabrication under duress and suggestion reveal a much more complicated—and manipulable—process at play with the formation of memories. From the relatively benign—getting lost in a shopping mall—to the relatively traumatic—being attacked by a vicious animal—researchers throughout the years have been able to successfully induce memories . . . that never actually happened.

These experiences have been coined in a variety of fashions, including "honest lies," phantom recollective experiences, pseudomemories, and autobiographical false memories.

A combination of confrontation, guilt-assumption, leading questions, the introduction of new and inaccurate information, and even just pressuring the interviewee to present details of a particular event can "facilitate false confessions and promote inaccurate witness accounts, which can ultimately lead to procedural injustice and wrongful imprisonment."

Worst yet? Recent studies have also proven that false memories become relatively indistinguishable from actual memories in both brain activity and emotional fallout.

Porter and Shaw's study focused on 70 college-aged students at a Canadian University; they were attempting to convince these individuals that they had committed a crime between the ages of 11 and 14. The students—who in turn were vetted by their caregivers, who confirmed that none of them had ever had run-ins with the police—believed they were participating in an examination of memory-retrieval methods. They filled out questionnaires detailing certain memories, and then were interviewed three times over the course of three weeks.

The interviewers immediately began introducing a fallacious memory, couched between actual accounts the participants had described themselves in their questionnaires. When the students failed to remember details about the false memory (imagine that!) the interviewers encouraged them to conjure details, explaining (falsely) that "most people can remember these kinds of memories if they try hard enough."

The participants were given "guided imagery" as well as "context reinstatement" and told to visualize the false event as they were going to sleep in order to help "retrieve the memory."

After just three interviews, 21 of the participants—or 70% of those "assigned" to a criminal memory (theft, assault, or assault with a weapon)—believed such an event had transpired, with rich details and reasonable confidence.

"Our findings that young adults generated rich false memories of committing criminal acts during adolescence supports the notion that false confessions and gross confabulations can take place within interview settings."

Porter and Shaw argue that future studies must be dedicated to the intricacies of interview tactics and the complicated social processes that are part and parcel of the formation of false memories. While their study was more directly focused on proving the prevalence and ease of creating pseudomemories, the implications of their findings cannot be overstated.

A closer examination of interrogation tactics would "make a significant contribution to understanding the effects of each of these tactics and how well they would map onto actual police behavior. The kind of research presented here is essential in the quest to help prevent memory-related miscarriages of justice."