Woman on the Edge of Time is considerably more complicated than The Handmaid's Tale. And that's a good thing.

Thirty years after it was first published, Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale remains popular, both with readers and with teachers. In part, this is no doubt because this particular nightmarish future remains a favorite nightmarish future. In The Handmaid's Tale, the bad guys are repressive, anti-sex, right-wing religious whackos who have conquered America—they're a stand-in for the moral majority of the Reagan era, a Christian right which is with us still. But those bad guys also reference Western visions of Islamic evils—the oppressed handmaids in Atwood's future America of Gilead wear what are essentially burkas, and there's a telling reference to "paintings of harems, fat women lolling on divans."

The Handmaid's Tale takes the repression and exotification of women of color and generalizes it to all women. The result is a fairly straightforward morality tale, in which (all) women are oppressed by a non-specific, generalized conservative fanaticism. You can see why that still resonates in a post-9/11 world, in which the egalitarian liberty of the West is often defined in opposition to "Islamofascism." The Handmaid's Tale can easily be read as a prescient warning against sharia law; the book is conservative in the sense that it takes a stand against an incursion of foreign values and foreign culture. It says, don't let those people make us over in their image.

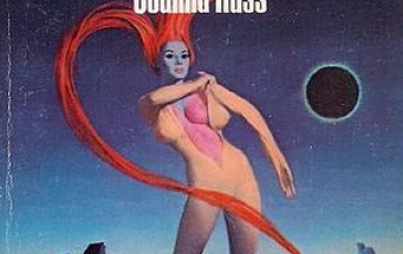

Again, that's the sort of message people like to rally around. So it's no wonder, really, that The Handmaid's Tale, as feminist dystopia, has largely eclipsed Marge Piercy's 1976 novel, Woman on the Edge of Time, in the popular consciousness.

Piercy's novel is considerably more complicated than The Handmaid's Tale in every sense of the word. Woman on the Edge of Time's central character is Conseulo (Connie) Ramos, a poor Hispanic woman.

The Handmaid's Tale sets its dystopia of white women's oppression in the future. But in Woman on the Edge of Time, the dystopia, for a poor woman of color, is 1976 plain and simple; there's no need to imagine a religious takeover, Christian or Islamic—the secular authorities of America are quite capable of inflicting brutal oppression themselves, thankyouverymuch.

Connie's life is a litany of state violence and terrorism. One of her lovers is shot by police; another is arrested for petty theft, and then dies in prison after volunteering for medical experiments in the hopes of getting out. Connie is plunged into depression, during which time she strikes her daughter; child protective services then take the girl, and put Connie in a mental institution. She begins having visions of a radically egalitarian utopian future embodied in a place called Mattapoisett, communicated to her by an androgynous being called Luciente from the future. It's not clear in the book, though, whether Connie actually travels to the future, or whether she is mentally ill; she is locked in an asylum for most of the novel.

Connie is eventually released, but never sees her daughter again. She's arrested once more when she strikes her niece's pimp to prevent him from beating her. The pimp knocks her unconscious, then gets the police to incarcerate her. While in the mental institution for the second time, Connie is herself the subject of medical experiments—the doctors put implants in her brain to try to control her emotions and moods and "cure" her.

Connie, in our world, is despised, policed, and brutalized because she is poor, and Hispanic, and a woman, and (perceived as) mentally ill. In contrast, in the future of Mattapoisett which she visits, distinctions of color, of sexuality, of class, and even of gender are radically rewritten. People live in small, close-knit communities; everyone rotates unpleasant jobs and then has time to focus on the things they love or are good at. Everybody who wants to, of whatever gender, can be a mother to a child; everybody forms the sexual relationships they want, as exclusive or open as they wish. If there are jealousies, or tensions, they are discussed at length in group meetings—a process that Connie finds tedious and invasive.

Indeed, there's a lot about the future that Connie finds disturbing. One of Piercy's most impressive achievements is that she shows just how much would have to change to create a just and equal world, and just how uncomfortable many of those changes would be. Connie is particularly horrified by the elimination of pregnancy; babies are grown in test tubes, and the particular bond between biological mother and child is severed. Connie, as a mother divested of her child, sees this as horrific. But her friend from the future, Luciente, explains that the change is necessary, for the good of women and of men. "Our dignity comes from work. Everyone raises the kids, haven't you noticed? Romance, sex, birth, children—that's what you fasten on. Yet that isn't women's business anymore. It's everybody's."

Despite her reservations, Connie is won over by Mattapoisett. But even utopian dreams, in Piercy's world, are ambivalent. Connie becomes convinced that she must use violence to ensure that the revolutionary future of Mattapoisett comes into being. As a result, she poisons a number of her doctors. These doctors are presented as condescending and casually brutal; they try to "cure" one of Connie's friends of his homosexuality, and end up driving him to suicide; on other patients, they use their brain control techniques with sadistic glee. Yet Connie's decision to kill them is still shocking, and also painfully futile. Does she gain anything by murder, other than her own continued imprisonment? Is she a freedom fighter, or is she simply delusional?

"The anger of the weak never goes away… it just gets a little moldy. It molds like a beautiful blue cheese in the dark, growing stranger and more interesting," Connie muses at one point, but it's not clear that anger leads to change rather than just to further pain.

The Handmaid's Tale ends by suggesting to us that the handmaid eventually made her way to freedom; Woman on the Edge of Time ends with Connie being shipped off to a different mental institution, presumably for the rest of her life, given that she's killed several people. She also loses her ability to travel to Mattapoisett. The future is closed; there is nothing but the injustice and cruelty of the present.

That's obviously not a particularly cheerful message, and Woman on the Edge of Time is in many ways a bleak book. There are a host of muddy bad guys; the true "enemy" is not explicit or specific: Connie's brother, who enjoys seeing her in a mental institution and won't sign her out; the doctors who want to experiment on her for her own good; the police system which offhandedly killed the men she loved; child-protective services. Connie's oppression is diffuse and casual, rather than spectacular; it's not clear who to fight, much less how to fight them. Hope, too, is wavering, uncertain.

And yet, Piercy's book also, at least to me, seems more hopeful, and more daring, than A Handmaid's Tale. Atwood's book, like 1984 before it, comes across as a kind of justification of the status quo; it focuses on totalitarian evils fulfilled elsewhere and (supposedly) only potentially, here and now. As a result, it can't see injustices of poverty, or race, or even of gender, in the world we live in, which means it can't imagine a way out of them.

Piercy, on the other hand, sees just how dire the present is, and still, in the book's most famous line, declares, "an army of lovers cannot lose."

The Handmaid's Tale will probably remain the story we want to hear, but Woman on the Edge of Time has a better grip on the present, and the future as well.