Gayle Brandeis

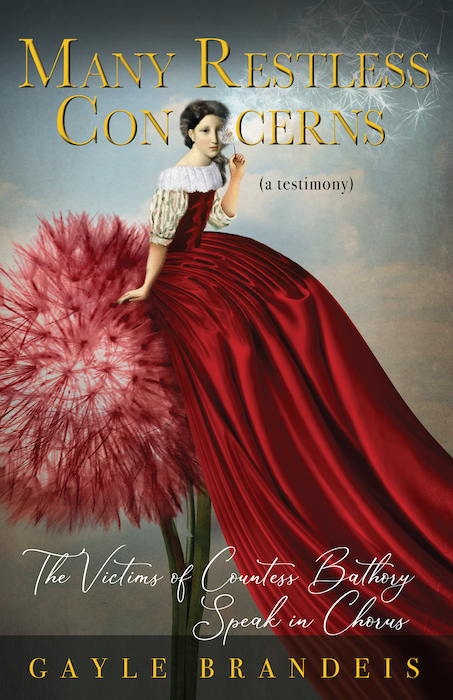

In her first novel in poems, award-winning author Gayle Brandeis gives voice to the hundreds of girls and women killed by Countess Erzsébet Báthory of Hungary between 1585 and 1609. The ghosts of these girls and women speak in chorus, compelling us to bear witness to the violence enacted against them and to share their quest for justice—not only for themselves but for all girls and women to come. A lyrical, polyphonic protest against silence, Many Restless Concerns speaks to today’s upswell of voices claiming their own worth.

Erin Khar: Your book is unusual in that it is a novel in poems. Tell me a little bit about how you decided to present the story in this way.

Gayle Brandeis: I find that writing projects will tell me their form (although it can take several drafts before that form reveals itself).

When I started this project, I thought I was just going to write a small series or cycle of persona poems, but the ghosts of these girls and women kept whispering to me, and I realized they demanded a larger story.

I started out writing lineated poems, and then at some point, revised them all into prose poems, and finally realized the book wanted to be a hybrid of the two and went through several drafts until the balance felt right.

EK: In what ways did the current cultural climate and the #metoo movement inform the storytelling in your book?

GB: I started writing the book in 2009, prior to the #metoo movement, and issues of the day didn’t enter my thoughts or process at the time; I just wanted to break a centuries-long silence. I set the project aside because I was pregnant then, and reading and writing about torture and murder while new life was growing inside me became too hard to stomach.

Then my mom took her own life when the baby was a week old, and every other writing project fell away as I focused on a memoir about her suicide and our relationship, trying to make sense of all of it. Once I finished writing The Art of Misdiagnosis, I felt so lost as a writer—it was the hardest and most necessary book I’d ever written. I didn’t know how any other writing project could ever feel as meaningful.

Then I remembered these ghost girls and women and threw myself back into their project. It took a while before I realized I was writing to our current day as much as I was writing about the past—their story speaks to the ongoing violence enacted against missing and murdered women (especially indigenous women), as well as to the power of women raising voices together, finding solidarity and agency together through movements like #metoo. Once I realized that the project felt all the more urgent. The rest of the book burned its way out of me.

EK: What books had the greatest influence on you as a writer and as a person?

GB: Oh my goodness, there are so many—I know I’ll forget some that are closest to my heart, so this is definitely not a complete list; I’ll just share the first few that pop into my mind right now. Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh was so formative to me as a kid, showing me the power of the notebook, the power of paying attention to the world around us, and giving it voice. The Dead and the Living by Sharon Olds gave me permission in college to tell the truth about my own embodied experience, and Diane Ackerman’s A Natural History of the Senses helped me celebrate this embodiedness and the sensory-rich world around us.

Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience informed me as a young activist, and Audre Lorde’s work deepened my political awareness. Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison—the first book of hers I ever read—showed me how much myth and magic can be threaded into our stories. More recently, Carmen Maria Machado’s work, both Her Body and Other Parties and In the Dream House, rearranged my molecules with their playfulness with form and their expansive dive into body and imagination.

EK: What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve received? What’s the worst?

GB: The best advice I’ve received (which I’ve heard from many people, but remember it first coming from Alma Luz Villanueva when I was getting my MFA) is to write about what scares us. I had often shied away from my own fear in my work as a younger writer, and this advice helped me feel brave, helped me realize writing about what scares us can be a way of both understanding and releasing these things, and helps us bring our full humanity to the page.

The worst piece of writing advice I’ve received (which I know some people consider the best advice!) is to write every day.

While I do see the benefit of this practice, and I do appreciate those spans where I am able to write every day, I’m not a machine, and I’ve found it’s advice that can lead to so much guilt and shame (at least in me) and doesn’t honor those fertile fallow periods where we need to step away from our work and allow ourselves to just be in the world so the world can seep into us and our writing afresh.

EK: What are you reading now?

GB: I’m (re)reading Faylita Hick’s powerful debut poetry collection HoodWitch after hearing her read from it at the recent Sierra Nevada College MFA residency (she’s an alum and returned to celebrate her book) and it’s leaving me breathless all over again. I’m also swimming through Jane Alison’s Spiral, Meander, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative, which is affirming my own mistrust of Freytag’s pyramid (introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, conclusion) which certainly works as story structure, but I’ve long thought it looks like a map of the male sexual experience and I was tickled to see Alison feels the same way. There are so many other ways of being in a body, of being in a story—waves and loops and the like—and she writes about other possibilities for narrative with great beauty and illumination.

Gayle Brandeis is the author, most recently, of the novel in poems, Many Restless Concerns: The Victims of Countess Bathory Speak in Chorus (A Testimony) (Black Lawrence Press). Her other books include the memoir The Art of Misdiagnosis (Beacon Press), the poetry collection The Selfless Bliss of the Body (Finishing Line Press), the craft book, Fruitflesh: Seeds of Inspiration for Women Who Write (HarperOne). She is also the author of several novels, including The Book of Dead Birds (HarperCollins), which won the Bellwether Prize for Fiction of Social Engagement judged by Barbara Kingsolver, Toni Morrison, and Maxine Hong Kingston. Her poetry, essays, and short fiction have been widely published in places such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, O (The Oprah Magazine), The Rumpus, Salon, Longreads, and more, and have received numerous honors, including a Barbara Mandigo Kelly Peace Poetry Award, Notable Essays in Best American Essays 2016 and 2019, the QPB/Story Magazine Short Story Award and the 2018 Multi-Genre Maverick Writer Award. She teaches at Sierra Nevada College and Antioch University Los Angeles.