Ever wonder why the hell the theater world's most illustrious award was called Tony? Us too.

Here's the lowdown: apparently the award was founded in 1947 by Brock Pemberton of the American Theatre Wing in honor of Antoinette Perry, nicknamed Toni, a still-revered actress and co-founder of the American Theatre Wing, who died in 1946. Perry was a beautiful badass who hailed from Denver; while women had previously been relegated to acting, costuming or choreography, she leveraged her tenacity and inherent business acumen to move from epic stage performances to an unprecedented career in directing and producing, making one hit after another.

At the initial event—held in 1947 at the Waldorf Astoria in NYC just a year after Perry's death—Pemberton handed out the very first award and called it a Tony. The name stuck and still stands.

Sadly, this year there's not a vagina-fueled play in sight at the Tony's.(Perhaps because not a single female-written play was produced on Broadway this year despite three female-written plays being nominated—and winning!—the Pulitzer this year. I mean, what gives people?) Poor Perry is grave-turning for sure.

To remember just how much the fairer sex has contributed to the world of theater, here's a handy 'lil round-up of Tony-nominated (and winning!) plays written by women.

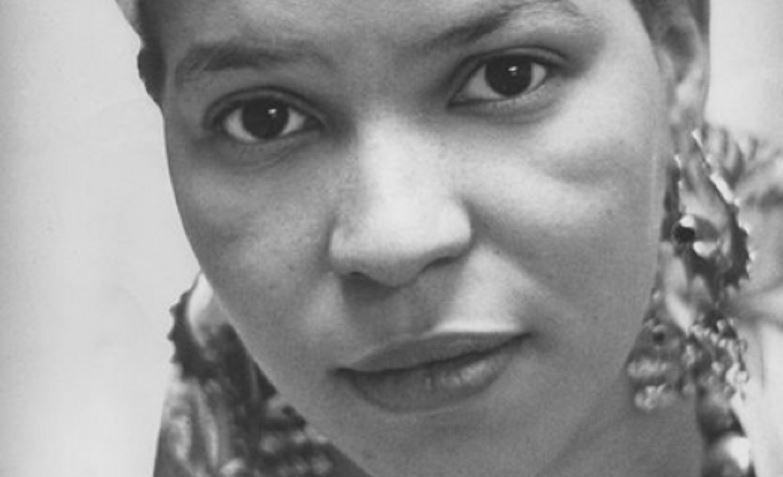

Lorraine Hansberry — nominated for A Raisin in the Sun in 1960

Hansberry's now iconic play takes its title from Langsten Hughes' famous poem, A Dream Deferred. "What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?" A Raisin in the Sun was not only the first play written by a black woman to be produced on Broadway, but also the first play on Broadway with a black director, Lloyd Richards.

All experiences in this play—which trace an African American's family's struggles with racial segregation in Chicago—echo a lawsuit (Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940)), that Hansberry's family actually endured. Hansberry described the harrowing litigation in her autobiography, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black. (Incidentally, Nina Simone also wrote and dedicated a song to Hansberry by this same title.)

25 years ago, [my father] spent a small personal fortune, his considerable talents, and many years of his life fighting, in association with NAACP attorneys, Chicago’s ‘restrictive covenants’ in one of this nation's ugliest ghettos. That fight also required our family to occupy disputed property in a hellishly hostile ‘white neighborhood’ in which literally howling mobs surrounded our house… My memories of this ‘correct’ way of fighting white supremacy in America include being spat at, cursed and pummeled in the daily trek to and from school. And I also remember my desperate and courageous mother, patrolling our household all night with a loaded German Luger (pistol), doggedly guarding her four children, while my father fought the respectable part of the battle in the Washington court.

The 29-year-old writer became the youngest American playwright and only the fifth woman to receive the New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play. Raisin in the Sun was so popular, over the next two years it was translated into 35 languages and was mounted all over the world.

Lillian Florence Hellman — nominated for Toys in the Attic in 1960

Hellman took three years to write her shadowy, semi-autobiographical play, which highlighted serious familial dysfunctionality tracing the relationships between two spinster sisters in New Orleans following the Great Depression; Hellman tackled everything from incest and race relations to the failed American Dream. Eerier still? It's said that Hellman based much of the play on her own life. Hellman apparently was sexually attracted to her own uncle, and her aunt had an affair with their African American chauffeur, both of which are explored within the confines of the taut play.

Hellman was also famously blacklisted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) during the fevered hunt for "commies" circa 1947-1952. Her comrades celebrated her utter commitment to the cause and tenacious refusal to answer any questions by the HUAC, though it was well-known she was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. She never named names, never decried the party and never apologized. Her letter to the HUAC in 1952:

...to hurt innocent people whom I knew many years ago in order to save myself is, to me, inhuman and indecent and dishonorable. I cannot and will not cut my conscience to fit this year's fashions, even though I long ago came to the conclusion that I was not a political person and could have no comfortable place in any political group.

I was raised in an old-fashioned American tradition and there were certain homely things that were taught to me: to try to tell the truth, not to bear false witness, not to harm my neighbour, to be loyal to my country, and so on. In general, I respected these ideals of Christian honor and did as well as I knew how. It is my belief that you will agree with these simple rules of human decency and will not expect me to violate the good American tradition from which they spring. I would therefore like to come before you and speak of myself.

Toys in the Attic, (while it lost to The Miracle Worker by William Gibson that year) won the New York Drama Critics' Circle Award for Best Play.

Ntozake Shange — Nominated for For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf in 1977

Shange's "choreopoem" (a term coined by Shange herself) is comprised of 20 poetic monologues designed to be accompanied by dance and music. For Colored Girls depicts the stories of seven interwoven women who are wrestling with everything from abortion, abandonment and rape, to domestic violence and the societal sanction of racism and sexism. The seven women within the play are nameless; their only identity is a color of the rainbow.

Shange was a vocal, self-proclaimed black feminist, though her involvement in fostering the actual Black Arts Movement—triggered by Malcolm X's assassination around 1965—is hotly debated, as her true focus was on women's issues as opposed to solely highlighting race.

The same rhetoric that is used to establish the Black Aesthetic, we must use to establish a women’s aesthetic, which is to say that those parts of reality that are ours, those things about our bodies, the cycles of our lives that have been ignored for centuries in all castes and classes of our people, are to be dealt with now. —An Interview with Ntozake Shange, by Henry Blackwell, Black American Literature Forum, 1979

Elizabeth Becker "Beth" Henley — nominated for Crimes of the Heart in 1986

Henley was Jackson, Mississippi born and raised; her plays are centralized around women, family and Southern life in America, often interweaving tragedy and comedy in unlikely ways. Crimes of the Heart was at the epicenter of all these aesthetics, centering around three sisters who reunite at their old house in the wake of one them shooting an abusive husband. While Henley first had trouble getting her play produced, a friend clandestinely entered it into the Great American Play Contest at the Actors Theatre of Louisville; the play won, received critical acclaim and proceeded to Broadway two years later in 1981.

Henley used her characters to discuss pressing societal issues including gender roles and identity, the confines of domestic familial life, the inherent loneliness and pain of the human condition, and the trappings of romantic love.

Crimes won the the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1981 in addition to Best American Play from the New York Drama Critics' Circle.

Wendy Wasserstein — won best play for The Heidi Chronicles in 1988

An ambitious play in that it tackles more than 20 years of one woman's life, the plot follows the trials and tribulations of Heidi Holland, all the way from high school in the 1960s to her establishing a successful career as an art historian two decades later. Wasserstein uses Holland's experiences to comment on the evolution of feminism in the United States—particularly in the 1970s—before "succumbing" to her own sense of betrayal in the 1980s.

Her heroines—intelligent and successful but also riddled with self-doubt—sought enduring love a little ambivalently, but they did not always find it, and their hard-earned sense of self-worth was often shadowed by the frustrating knowledge that American women's lives continued to be measured by their success at capturing the right man...women who embraced the essential tenets of the feminist movement but didn't have the stomach for stridency. — Charles Isherwood, New York Times

Although Wasserstein died rather young from lymphoma in 2006, her work had already spanned four decades and 11 celebrated plays that brilliantly dissected the modern age and women's ongoing "identity crisis." The Heidi Chronicles also won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1989.