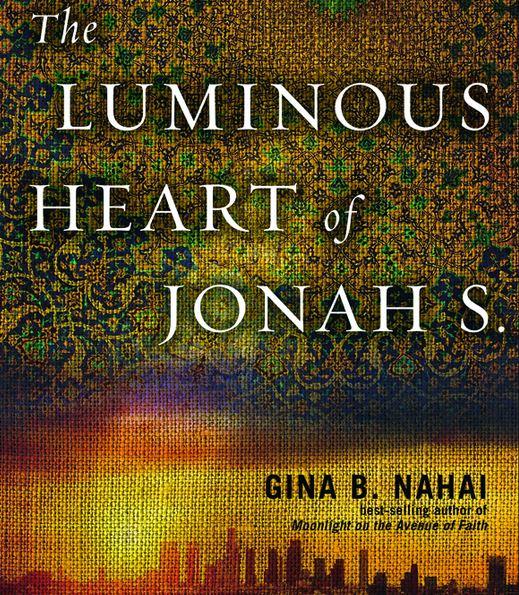

Born in Iran and educated in Switzerland and the U.S., Gina B. Nahai brings a worldly perspective to her acclaimed novels, often exploring the lives of Iranian Jews.

Her books—including Moonlight on the Avenue of Faith, Sunday's Silence, Cry of the Peacock and Caspian Rain—have been translated into 18 languages, and selected as “Best Books of the Year” by the Los Angeles Times and the Chicago Tribune. She has also been a finalist for the Orange Prize, the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and the Harold U. Ribalow Prize, and has won the Los Angeles Arts Council Award, Persian Heritage Foundation’s Award and Simon Rockower Award. She is also a full-time lecturer at the University of Southern California's Master of Professional Writing Program.

Nahai's latest book, The Luminous Heart of Jonah S., is being published by Akashic Books, and will hit shelves October 7. It tells the tale of an Iranian Jewish family in Los Angeles that's been tormented for decades by Raphael’s Son, a crafty and unscrupulous financier who has futilely claimed to be an heir to the family’s fortune. Forty years later in contemporary Los Angeles, Raphael’s Son has nearly achieved his goal—until he suddenly disappears, presumed by many to have been murdered. The possible suspects are legion: his long-suffering wife; numerous members of the Soleyman clan exacting revenge; the scores of investors he bankrupted in a Ponzi scheme; or perhaps even his disgruntled bookkeeper and longtime confidant.

Ravishly got an exclusive first peek at the book, and shares an excerpt here.

***

She went home and told her parents she had found her future husband. He was the man who lived in the Big House, she said, the one all the women wanted for their own daughters. He had called her “little one” because he didn’t know her name, and he had not addressed her again or even appeared aware of her presence until she went up to him after midnight to take her leave. She extended her hand to him and said, “Thank you, sir. You honored me by this invitation,” which seemed to have surprised him, she told her parents, because he had pulled his head back a little, narrowed his eyes, and examined her as if for the first time.

“Such big words for a little person,” he had said, and only then did he take her hand and shake it. Letting go, he peered down at his palm, as if searching for the source of the scent, and then he turned to her again, this time with fascination.

“You smell like the north,” he had said.

***

Her parents, then, might have tried to explain to Elizabeth the dangers of giving her heart so quickly and at such a young age, especially to man who, by her own testimony, took not the slightest bit of interest in her, but they were busy fighting the small flood that had poured out of a broken pipe somewhere underground and was spreading throughout the house with alarming speed. Unable to pinpoint the source of the water, they sat up all night and watched it rise around their feet and ankles and all the way up to their knees, so that the furniture was floating around in the rooms and the children had to be sent onto the roof to sleep. In the morning they called a plumber, then a contractor, then the original architect of the house, and when none of them managed to stop the water, they dug the ground to where the pipes came in from the street and filled them with cement.

That stopped the flood, and ushered in the drought.

For weeks, the family’s furniture, their clothes and books and the children’s toys, lay in the yard waiting to dry. Surprised by the incident and eager to defend the soundness of the house he had sold, Aaron insisted on paying for all the damage and the cost of repair. He knew there was nothing wrong with the plumbing, and that he had no legal obligation to fix anything. But in a world where a man’s word was his best asset, and where one’s name and reputation outlived him for generations, it was essential that he make good on what he had represented in the sale. He ordered the old pipes dug up and new ones laid, replaced all the faucets, repaired the damage to the paint and the moldings and the floors. The day the furniture was moved back in, the new pipes went dry.

So began the Battle of the Pipes that would plague Raphael’s house for as long as Elizabeth’s family lived in it, and that mystified Aaron and the rest of the city. No matter what remedy was applied, the house was alternately flooded or without running water, the yard soggy or scorched. The storage tank was infested by the decomposing bodies of stray cats and giant, thirsty rats that managed to fall into it even with the hatch closed. Mold set into the damp walls and wooden furniture rotted, dishes piled up in the sink and clothes remained unwashed because the water had suddenly stopped flowing to the house, and it got so bad, caused so much disruption, it became the subject of constant chatter and ceaseless speculation around town.

Manzel the Mute was convinced it was the work of the ghosts and spirits that had gathered around Raphael for so much of his life. Left orphaned when he died, they must have crawled into the pipes or fallen into the well to escape the light, causing trouble every time they moved. Other people, more educated than the maid and therefore less given to ghost stories, speculated instead that the house had been cursed by Raphael’s Wife when she was forced out of it, or that—this one enraged Aaron more than the rest—he was being punished by the Almighty for having sinned against an old woman by turning her out when she had nowhere to go.

Aaron hated superstition, and he was exceptionally sensitive to the suggestion that he might have done wrong to the Black Bitch. In part, this was because he was certain he had been more than fair to her. He also worried about the damage to the family name if people’s perception was skewed in the witch’s favor. But there was also that distant, nagging fear, the voice of his mother and grandmother and all the other women he had known as he was growing up and who often spoke of the hardships they had endured at the hands of their husbands and fathers. Those women spoke of something they called aaheh zaneh beeveh—the widow’s sigh. They said it was a black wind that blew from the darkest corners of the universe to punish those who broke a widow’s heart. It was, the women insisted, all that guarded the weak from the mighty, a cosmic justice that could strike anywhere, at any time—the righteous hand of destiny exacting revenge on those who transgressed the unwritten rules of mercy.

***

The scent Aaron had detected around Elizabeth, that he said reminded him of the north, hung in the air long after she had left that first Shabbat evening in her saddle shoes and gray, pleated skirt. It was all he would remember about her from that first meeting—that, and her oddly adult mannerisms and language. The rest he forgot the minute he turned from her to his other guests.

But at home on Saturday evening, he smelled the Caspian in the hallway leading from the main door to the kitchen, and for a moment remembered a pair of white kneesocks and a large satin bow. On Sunday, he noticed that the air outside the Big House was more humid than anywhere else in the garden, and after that he kept encountering that scent in odd parts of the house or around it, on a rug or a curtain and once even in the rice the cook had prepared especially for him. He called the cook into the dining room and complained—there’s a limit to how much salt and fish you should put into the food—but the poor man had no idea how to explain the scent; he mumbled for a minute or two and finally promised it would not happen again.

He made the same promise the next time Aaron ate at home. The following occasion, he washed the rice seven times instead of the usual four, boiled the water once before pouring the rice into it to boil again, and handled every step of the making of the duck-and-pomegranate stew himself to make sure nothing would be contaminated. When Aaron sent the food back, complaining that it smelled like seawater, the cook finally marched into the dining room in his turmeric-and-saffron-stained shirt, rubbed his two-day-old stubble down with the front of his apron, and said, “I can’t lie to you, agha—sir—it’s that girl who snoops around here every day that brings the smell.”

What Aaron didn’t know was that Elizabeth had spent every weekday afternoon and all of Friday in his house, starting the day after his first invitation, and that she was planning to remain there for as long as it took to become of age, marry Aaron, and make the house her permanent home. She came straight from school with her book bag and stacks of loose paper, and she stayed in the kitchen where Manzel, herself a lonely teenage girl with no real family, let her spread her books and pencils and compasses and protractors on a small table in the farthest corner from where the cook worked. The cook had let her stay at first because she was polite and self-effacing and really no trouble to anyone at all, but after a few days, when he realized that her scent was permanent and overpowering, he had sent her home to bathe “until you smell like a normal person.” Still, she came back the following afternoon dragging the sea behind her, content only to catch a glimpse of Aaron, or hear his voice, before the cook shooed her away.

Aaron sent word to the professor to restrain his daughter, and the poor man did all he could—sat her down and gave her the this-is-an-embarrassment-for-your-mother-and-me, think-of-our-aabehroo-if-not-your-own talk—but his feeble attempt at exercising his parental authority was interrupted by yet another explosion of the pipes and the subsequent flooding which, they all knew by now, would engender a drought.

***

By 1967, the Battle of the Pipes was in its fifth consecutive year and raging as fiercely as ever. The uncertainty of what may happen next and the bedlam caused by each eruption of the pipes had turned the twins into a pair of agitated, faltering, forever distrustful creatures who clung to their father unceasingly and sapped every bit of strength from him. The father, in turn, was so perturbed by the constant traffic of plumbers and bricklayers and painters and upholsterers who came to restore the flow of water to the house or to clean up the debris once it had started to flow, he had lost thirty kilos and taken to drink. Madame Doctor stayed at her clinic as much as possible, the twins were increasingly unhinged, and Elizabeth had become a de facto resident of the main kitchen in the Big House. He asked the gardener to trim all the trees and uproot all the plants and flowers on the immediate periphery, and hired two men to scrub every wall and ceiling and floor, every cabinet and dresser drawer, window and tabletop and mirror, with white vinegar mixed with water. He had all the rugs taken outside and beaten with wooden sticks, then washed and left to dry; he installed new curtains, changed the cotton stuffing of his own mattress and the down in his pillows.

When she wasn’t doing homework or burning through college-level math and science books for fun, Elizabeth helped Manzel with her chores, then sat her down and insisted on teaching her to read and write. It was an extraordinary scene: the mute village girl in plastic flip-flops and old hand-me-downs sitting next to the teenage professor in the white dress shirt with rounded collars, both of them bent over a notebook with lined paper as if to unearth a secret. An illiterate and a prodigy, a Muslim who had been taught that Jews are ritually impure and a Jew who didn’t have the first clue about her own religion but who could recite the entirety of the Muslim namaz in Arabic.

In spite of their differences, each was the other’s only friend, the closest she would come to having a protector. Manzel was the one person in the world who made sure that Elizabeth had eaten breakfast or lunch each day, checked if she wore dry socks to school or put them on wet and moldy from the latest flood. Elizabeth used her pocket money to buy Manzel chewing gum and sour fruit rolls and other treats from street vendors that were not allowed in Bagh-e Yaas. She brought her children’s books and glossy cutouts from women’s magazines and pencils with white erasers attached at the end, made lesson plans and assigned homework and conducted each study session with utmost gravity.

In the end Elizabeth became so much a part of life in the Big House that it seemed she had been born there. Her parents gave up on trying to salvage her pride or good manners and retreated ever further into the background, and Aaron got used to the scent.

Then the Black Bitch of Bushehr came back to sully it all.

***

Stay tuned for more exclusive book excerpts, and read our first look at Carrie Mesrobian's Perfectly Good White Boy here.