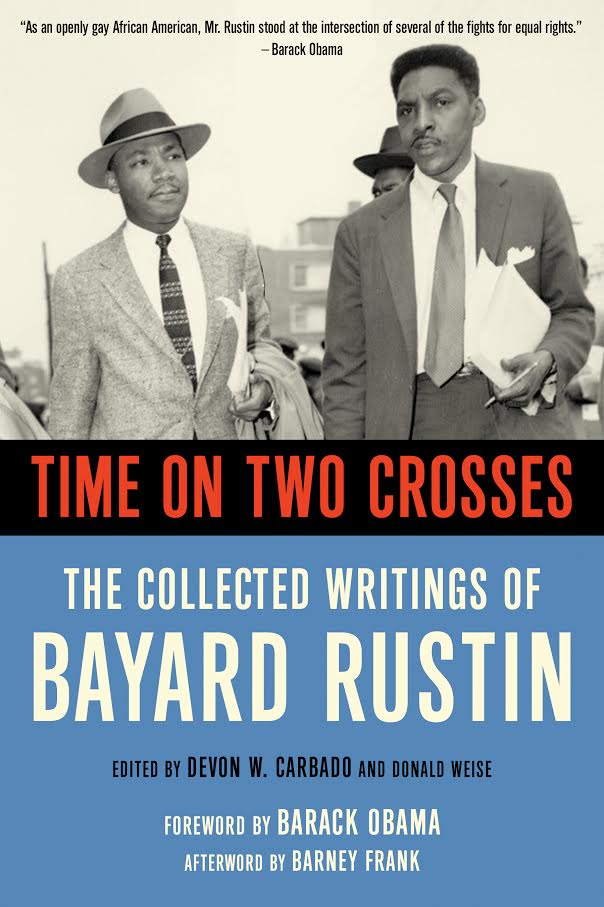

Time on Two Crosses: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin explores the work and life of one of the most remarkable men of the civil rights movement—an openly gay African American organizer who, as President Barack Obama puts it in the forward for the book, "stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights." It was Bayard Rustin who introduced Martin Luther King Jr. to the precepts of nonviolence during the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and who organized the momentous 1963 March on Washington. These strides were made despite Rustin's homosexuality putting him in the crosshairs of controversy within the black church—often involving King himself.

In this excerpt from the book, Rustin opens up about King's views on gay people, as well as his own struggles in becoming director of the March on Washington.

***

IT IS DIFFICULT FOR ME TO KNOW what Dr. King felt about gayness except to say that I'm sure he would have been sympathetic and would not have had the prejudicial view. Otherwise he would not have hired me. He never felt it necessary to discuss that with me. He was under such extraordinary pressure about his own sex life. J. Edgar Hoover was spreading stories, and there were very real efforts to entrap him. I think at a given point he had to reach a decision. My being gay was not a problem for Dr. King but a problem for the movement.

He finally came to the decision that he needed to talk with some people in his organization. Reverend Thomas Kilgore, a good friend of mine and pastor of Friendship Baptist Church, was a man Dr. King turned to. Reverend Kilgore asked Martin to set up a committee to advise him. The committee finally came to the decision that my sex life was a burden to Dr. King. I think it was around July when they advised him that he should ask me to leave. I told Dr. King that if advisors closest to him felt I was a burden, then rather than put him in a position that he had to say leave, I would go. He was just so harassed that I felt it was my obligation to relieve him of as much of that as I could. Someone sent his wife a tape in which he was supposedly having an affair with another woman.

There was also another problem: some of the people in the Democratic Party were distressed at Dr. King's marching, as he did in 1960 and in 1964, against the conventions of both of the major parties calling for more immediate relief to black people through Congress. Adam Clayton Powell, for some reason I will never understand, actually called Dr. King when he was in Brazil and indicated that he was aware of some relationship between me and Dr. King, which, of course, there was not. This added to his anxiety about additional discussions of sex.

I don’t want you to think that Dr. King was the only civil rights leader who raised these questions. Although Dr. King had been relieved by my officially leaving, he continued to call on me as Mr. Garrow makes clear in his book, Bearing the Cross, over and over. Now this all took place around 1960; but in 1963 when the question came up whether I should be the director of the March on Washington, I got 100 percent cooperation. On this occasion, it was Roy Wilkins who raised the question. Roy was my friend. He told me he was going into the meeting to object. He made it quite clear that he had absolutely no prejudice toward me or toward homosexuality; but he said: “I put the movement first above all things, and I believe it is my moral obligation to go into this meeting and say that with all of your talent, I don’t think you should lead this important march. They are not only going to raise the question of homosexuality. Although I know you are a Quaker and I know you paid a heavy price for your conscientious objection, they are going to call you a draft dodger.” He was referring to my three years in prison as a conscientious objector in 1943, ’44, and ’45. “But,” Mr. Wilkins also said, “you were once, and you’ve never said you weren’t, a member of the Young Communist League. Therefore, they are going to raise three questions: the question of homosexuality, the question of draft-dodges, the question of your being a Communist. The fact that you are a Socialist is a problem, because people in the United States don’t differentiate between Socialism and Communism.” We also had a long discussion about how the Communists had co-opted the term Socialist, although the two systems are totally different: one is democratic and one is totalitarian.

Mr. Randolph [who was president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and president of the A. Philip Randolph Institute] took the view that it was important for him to have me. Mr. Randolph was finally made director of the march. “But I want to warn you before you vote that if I’m made leader, I’m going to be given the privilege of determining my staff,” he said. “I also want you to know I’ll make Bayard Rustin my deputy.” He turned to Martin and said: “Dr. King, how do you vote?” And Dr. King said: “I vote yes.” He turned to Jim Farmer. Jim Farmer said: “I vote yes.” Then he turned to Roy Wilkins. Roy said: “Phil, you’ve got me over a barrel, I’ll go along with you.” So, it was never a prejudicial situation; it was that given the attitude at that time, people felt this was a problem. I think there were others who felt: How many problems can a guy have and expect us to elevate him to the directorship of this march?

-From an interview conducted by Redvers Jeanmarie, March 1987

*Courtesy of Cleis Press