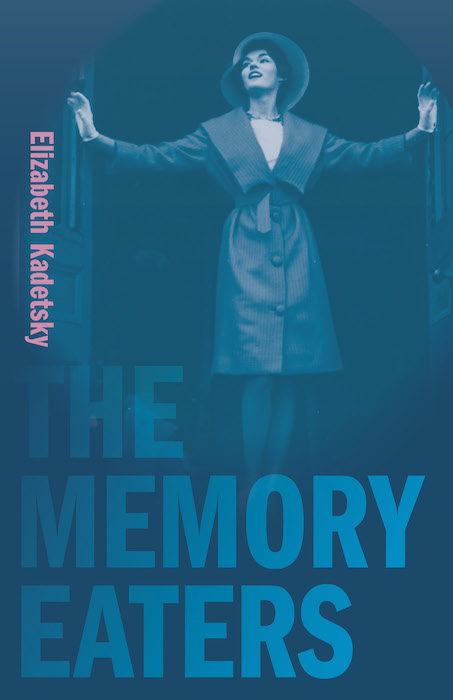

From the author's mother's modeling dossier, courtesy of Elizabeth Kadetsky.

I recently had the pleasure of chatting with Elizabeth Kadetsky about her memoir-in essays, THE MEMORY EATERS (University of Massachusetts Press, March 31, 2020), which explores family illness, addiction, inherited trauma, and the secrets of her inherited past. She is author of the memoir First There Is a Mountain, the short story collection The Poison that Purifies You, and the novella On the Island at the Center of the Center of the World.

About The Book

On autopsy, the brain of an Alzheimer’s patient can weigh as little as 30 percent of a healthy brain. The tissue grows porous. It is a sieve through which the past slips. As her mother loses her grasp on their shared history, Elizabeth Kadetsky sifts through boxes of the snapshots, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, and notebooks that remain, hoping to uncover the memories that her mother is actively losing as her dementia progresses. These remnants offer the false yet beguiling suggestion that the past is easy to reconstruct—easy to hold. At turns lyrical, poignant, and alluring, The Memory Eaters tells the story of a family’s cyclical and intergenerational incidents of trauma, secret-keeping, and forgetting in the context of the 1970s and 1980s New York City. Moving from her parents’ divorce to her mother’s career as a Seventh Avenue fashion model and from her sister’s addiction and homelessness to her own experiences with therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, Kadetsky takes readers on a spiraling trip through memory, consciousness fractured by addiction and dementia, and a compulsion for the past salved by nostalgia.

Erin Khar: Place plays a significant role in your essays. Do you think of New York as another character in the book?

Elizabeth Kadetsky: Thank you for this question! I do think of New York City as a character in The Memory Eaters. At times, I argue with the notion that place can be a character because I am always remembering those truisms that I learned in writing workshops about character: plot springs from character; a story is a sequence of events in which a character undergoes a transformation, etc. I often ask myself, can this place go through a transformation, does it have a fatal flaw, does it begin a certain way at the beginning of the narrative and end differently, does it drive the storyline? But if you look at New York City between the 1970s and the 2000s, well, the answer is yes. Applying this rubric, I’d say that, definitely, the place drives the story. The place goes through a transformation. And it certainly has several intriguing fatal flaws.

While writing The Memory Eaters, I found myself compulsively visiting sites of change in New York City—Union Square Park, my old apartment building and the diners in my old neighborhood, MoMA, subway stations that now served different train lines than they did in the 1970s and 80s. The constant rebirth of New York City and its neighborhoods and even subway lines was such a dynamic reality for me while I was writing as if that past that I was trying to catch hold of was slipping away as I watched. There was new demolition on every street corner, there always is. If you go back to a favorite block, particularly in Manhattan, even a year later, certainly, at least one shop or building will have been completely transformed. The Memory Eaters covers a 40-year period in the life of this kinetic place, from 1975 to 2015, more or less. The writing of The Memory Eaters represents my interaction with not only several different moments across this history, but the fact of its changing persona and characteristics over time, and my coming to terms with the loss of its past. You might say that memory is a character as well—as is the site of that memory.

Erin: As a memoir writer, I know how challenging and emotionally draining it can be to write about trauma. What advice would you give other writers who write about painful episodes in their life?

Elizabeth: I really appreciate how you have written about your painful history of emotional escape through drugs, and then your pulling yourself away from them. During the traumatic events that I describe in The Memory Eaters, I kept diaries as a kind of coping mechanism, to both process what had happened, and to “put them to bed,” in a sense. Everyone is different, but I have always found note taking to be a calming activity during such crises. That said, I did find it draining to go back over those notes after the fact. I’d put the events to bed, and then I had to wake them up again to shape them into actual writing. That, too, though, was in the end grounding and helped me distance myself from the feeling of actual trauma. So, my advice, which won’t work for everyone, is to do just that, to keep records as possible, and to then put them down while taking time to go through what healing is available. Then, one can revisit the material later.

Going through therapy also helped me approach those events with enough distance to work them into my actual writing project. So, therapy is high up on my advice list. After my assault, I was lucky enough to have access to several different forms of it. One of them is, again, not for everyone, but exposure therapy in particular trained my mind to see what had happened in a logical sequence that circumvented the jumbled, wordless emotions associated with it. This, in turn, gave me a feeling of mastery over what had happened and how I would allow it to affect me now. In my writing, I wanted to be true to the non-narrative, repetitive nature of my actual recollections of the event right afterward, but in reality, I had achieved an ability, through therapy, to see it differently. While not advocating for a dissociative relationship to one’s traumatic past, I also think that gaining perspective can help one to write about trauma without having to re-enter a traumatic mind state. This in itself can then, in turn, overall feed healing from the trauma.

Erin: In writing the book, what did you discover about epigenetics that you didn’t know before, and what do you want others to understand about epigenetics?

Elizabeth: I had read many articles that mainly tied epigenetic trauma to Jewish history. To back up, epigenetics is the scientific hypothesis, backed up in studies, that certain dormant genes or genetic tendencies can be “switched on” by environmental factors such that the gene in its “on” position then permanently alters a person’s genetic makeup and is passed on in that state to future generations. Surviving a famine is one oft-used example—a grandchild of a famine survivor might suffer lifelong problems regulating blood sugar. This scientific notion of epigenetics has been applied in the idea that survivors of the Holocaust possibly had genes that were triggered during the extreme distress and despair of the time, and that those “switched on” genes have been subsequently passed on to children, grandchildren, etc. This syncs up nicely and metaphorically with the pre-existing notion of something called Post Holocaust Stress Disorder, which has long been believed to affect children and grandchildren of survivors.

I’d read up on the topic because of my Jewish heritage, but in the end, I found the concept more applicable to my heritage on the other side, through my French Canadian mother. My immediate Jewish family had already left Europe by the time of the Holocaust.

So that is one new insight that came out of my writing the book, that though I knew about epigenetics, I’d never fully grasped how relevant the idea can be to other communities and even families. My mother’s family, with its history of alcoholism and its encounter with the brutal Canadian landscape not to mention the grueling circumstances of its immigration to the US in the early 1900s, seemed ironically more susceptible to literal or metaphorical epigenetic echoing than was my Jewish one.

So, I hope that non-Jewish writers—not to mention non-Holocaust-descended Jewish writers—feel empowered to use this resonant concept in their work and probings of family history. For one, many other groups have undergone mass trauma, for instance, descendants of slaves. Second, there’s often this misconception that trauma has to exist on a mass scale to be written about with power or legitimacy, but that is really not true.

Erin: What’s the best writing advice you’ve received? What’s the worst?

Elizabeth: As a graduate of not only an MFA fiction workshop but also a master's journalism program, I’ve gotten a lot! It’s hard to choose. The writing suggestions that I think about almost every time I’m composing are show don’t tell; use fewer words; add billboard sentences; avoid cliched phrases and irrelevant metaphors; be aware of arc.

But the one that is, perhaps, most helpful to newer writers is one I learned in journalism school. Don’t be fussy about your writing practice. That special notebook, that special pen, that special desk with that special window, that special hour of the day—all of those requirements will become unavailable when you most need to keep a record of your ideas and of what’s happening: if someone is dying, if you’re coping with the aftermath of a natural disaster, if you’ve just had a baby, if you’re involved in an intervention for someone else or yourself. In journalism school, I learned to write quickly to meet a deadline, even if it meant composing my story on the subway ride back after a reporting trip. So, have a notebook and pen or mobile notetaking device at all times, and when you have that thought, I should write that down, but I’m too exhausted, try very hard to listen to the good angel and get it down.

As for bad advice, it was a wonderful writer who shared this, but I do reject the notion that you can’t write about dreams, or that if you do, you are only allowed three in your entire life as a writer. My mother was an acolyte of Jungian philosophy, so this definitely doesn’t work for me. My whole writing process relies on dreams. When I’m in a state of cataloging events, particularly during a crisis, my notetaking always includes resonant dreams as well. Many of these make it into my finished work.

Erin: What are you reading now?

Elizabeth: Harry Potter is literally playing on audio in the background, for my five-year-old. We’re also reading it on the page. Kidding aside, from a writing craft perspective, I’m glad to finally be reading it because my undergraduate and graduate creative writing students are so hugely influenced by it. I am working on an argument in my head for everything Harry Potter doesn’t teach you about being a good writer for adults. It really lacks an inner story. For kids, though, it’s nicely clear and well structured.

For me, I am re-reading Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers. This book eschews narrative linearity while being true to the author’s experience of trauma. It is also extremely frank, plain-spoken, and brave. The simplicity of the prose allows for the occasional figurative language to really ring: My grandfather entered my life like lava, incinerating everything in its path. That incredible sentence would lose its power if cluttered by clichés, purple prose, and excess metaphor.

About the Author

ELIZABETH KADETSKY is the author of the memoir First There Is a Mountain, the short story collection The Poison that Purifies You, and the novella On the Island at the Center of the Center of the World. A professor of creative writing at Penn State and nonfiction editor at the New England Review, she is the recipient of fellowships from the Fulbright Program, MacDowell Colony, and Vermont Studio Center.