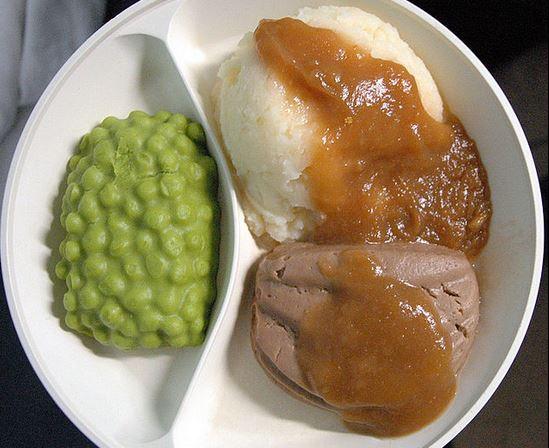

This? Not OK (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

Within the genre of "creepy habits you develop in art school," a weekly ritual of cooking a dish served as a prisoner's last meal skews relatively innocuous. Nonetheless, I have the requisite overly long and intellectualized justification for my habit.

Food, and the consumption of it, allows us to establish the rules for how we, in a sense, preserve our boundaries and consent as sentient beings, which in turn informs how we expect other people to treat us and our bodies.

The right to decide what goes into our bodies is integral to our dignity and self-care—and some of us are only afforded it right before the state murders us.

There isn't a single significant person in my life who has not struggled with self-harm, addiction or any other involuntary, internally coerced loss of control. And a great many of them would attest—if it was them writing this and not me—that if that loss of control brings you to the hospital or the jail, that covenant with yourself and your body will be shot on sight.

Tuna salad as a "vegetarian option." Diabetics forced to finish their fruit punch. A comically contrived predicament for the disbelieving is a real-life waking horror for the thousands who are admitted to psychiatric hospitals in America. You'll lose weight and grow a beard and daydream of pissing yourself just to break the monotony.

And the cruel indifference doesn't end there. Studies show that the mentally ill are three times more likely to be incarcerated, because that's where the money and beds are. And the food there isn't any better—though it could be deemed more "organic."

I don't want to heap grievances on abstractions—when I say "capitalism" or "prison industrial complex," I fear it enables the excision of personal responsibility from the occasion.

Call it what you will: We have a cultural contempt for those who "need" food—the poor, the infirm, the incarcerated. We take to Facebook in a rage when we see someone paying with food stamps. We write all-you-need-to-knows about prison food on trendy websites as an ironic exercise in celebrating our privilege. We set up websites where you can pay $60 for a care package of potato chips for someone you love who's on the inside, someone who, for my money—all $23 of it sitting in my savings—doesn't belong in a cage, fed maggot-infested Salisbury steak, but in counseling.

In cooking school, I was taught that people are poor because they eat too much enriched flour, and that my diabetes could have been prevented if I had eaten more celery as a child. My "final project"—pan-fried pork loin over a bed of stir-fried vegetables and rice—was given the top-most marks of the class, but at the cost of commentary on how a "serious" cook avoids condiments because "who knows what Asians put in that shit."

I was offered an apprenticeship: two years of private attention with chefs and nutritionists. I threw it on the ground. Literally. I hooked up my printer, printed the PDF and crumpled up the letter of admittance in front of one of the other apprentices.

I now work under the table at a local mental health clinic, on a rotation of cooks providing daily meals for 30-plus people. Corn chowder. Red beans and rice. Green beans and tomatoes. Vegetarian dishes that appeal to a "neutral" palette that help people on psychiatric medication maintain a steady blood sugar throughout the day.

Food is transformative. It creates community, it alleviates bad days. I remember the first meal I ever shared with my girlfriend. It's not an integral component of our relationship identity but it's there, an anchor when I feel far from her.

When you treat food as some placatory chore and openly deride poor/sick/incarcerated people who have access to nutritious and delicious food that enables them to have better relationships with their own bodies and in turn, the bodies of others, you set us all up for failure.

You and I need to take an interest in this. Because the people we've entrusted? Fuck, man.

Only about two-fifths of American medical schools require the recommended 25 hours of nutrition education. Only about one-third even offer a separate nutrition course. These people on whom we've built our (white) Western worldview of "health"—the people who are supposed to oversee the care of some of the most vulnerable of our society—don't know a whole bunch about what should go in our body (or care enough for your input).

I have appreciative clients, clients who ask the staff to send me texts and emails saying how good my cooking is—pffft, I know it!—and I'm unlikely to move into the private sector to feed chumps like this fucking guy anytime soon. Cooking is science. It combines biology, physics and chemistry into something you can make into poop on that awkward first sleepover at your girlfriend's house. It's wondrous and terrifying and frankly wasted on people who buy $12 tacos, when there are so many people who desperately need people who actually know about how food works to help them create a safe and sustainable relationship with their bodies.

But I'm doing a thing. I'm making a difference—not much of one, but a difference. And you could be making one, too, if you wanted. If you're really concerned with all these criminals and people on the dole in America, then maybe ring up your local kitchens and food banks and clinics and see what you can do (or drop off without anyone seeing you) to help create a better cultural relationship with food that better allocates it for the people who need it the most.

And, if you're curious: this week is soup, toast, meat and tea, the last meal of Sacco and Vanzetti.