Welcome to Freaky Film Friday. Our resident "creep whisperer" DoubleCakes has found a TV special that hits her where it hurts: 1989's Child of Rage, a documentary about an abused child who disconnects from the world around her.

"Does your brother have private parts?"

On any other day, this would be the Double Jeopardy for the "Last Words You Hear Before You Are Murdered" category. Instead it's from the recorded therapy sessions of Beth Thomas, a 6-year-old with reactive attachment disorder whose room is locked at night because she openly desires to murder her brother and adoptive parents. So maybe the $600 square.

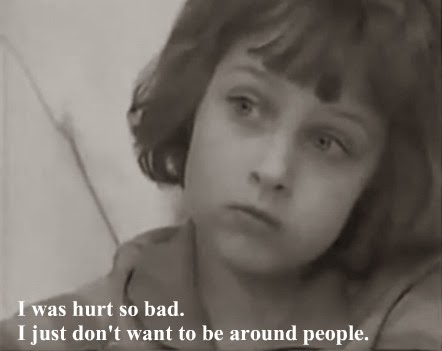

Beth is a victim of sexual abuse. This does not define her, and no child should have that as their primary "trait" when being introduced or described to another person.

But in light of the narrator's grim and repeated assertions that she is a child who "cannot love" and "cannot feel," I feel it prudent to remind you, the gentle viewer, that she is a human being who feels genuine, immeasurable agony over the hurt committed upon her.

Female sociopathy is the final boss of rape culture. A woman without empathy is a woman who cannot be coaxed into compliance, who cannot be controlled. Thus, our society has evolved to contain contrarian women by stamping them "emotionally disturbed," which discredits and mires them to a tight rope of tedium. Where's the balance between "overly emotional" and "sociopathic"? Well, we couldn't tell you—then you might fake it.

It's a comfort to lose ourselves in the swoon of sensationalism: "Behold the broken child who masturbates in public and yet cannot love another person." What if we affixed that unflinching gaze cast on her confession of killing baby birds onto the origins of her suffering—who did this, where are they, why did they do this and how do we stop them from doing this to someone else?

Beth Thomas is not the other. She is not the outlier. The producers try, in saturating the viewers in the salacity of her remorseless violence, to draw a chalk circle around her and say to us, the viewers, that it'll all be OK as long as we don't let her cross the line. But to shake your head at Beth and count your blessings is to blithely gaze at your own navel.

Beth Thomas is society—4% of it, anyway. That is the current estimate of the prevalence of sociopathy in our population. It is likely much higher. Sexual and child abuse is a known "cause," for a lack of better term—between four and five children die from abuse and neglect every day. Those of us who survive are left to protect ourselves any way we can—and sometimes this means just detaching entirely (though that's not a conscious choice).

"Us." I use this because I am a diagnosed sociopath. I have no sensation of empathy. I believe it's there, somewhere, but I do not "feel" it. People mistake and conflate it for compassion, love—these are not mutually exclusive. I have a lot of compassion. I have a lot of love. These things—and a zest for the dire and dangerous—compelled me to take up social justice. I worked as a street medic, I started a local Food Not Bombs, I even enrolled in school to become a therapist. Because I like it. Because it's fun. Because helping people feels good—even if I cannot fathom their emotional state.

My lack of empathy is perhaps what drove me to become a consent educator. I enjoy things that, when done without negotiation, without consent, can cause hurt and damage that are never repaired. It's necessary, when you can't "gauge" the emotions of another person, to be explicit—even clinical—in ensuring they feel safe with you and what you wish to do with and to them.

People like me make good therapists. And medics. Advocates for justice. A violent, patriarchal society relies on those with a fast and loose hold of empathy to handle the triage, to clean up the mess.

A lack of empathy, or the ability to distance yourself from it, is not a gift.

I'm not bulletproof. I could use a hug sometimes, too.

Beth Thomas' "recovery" is somewhat atypical—as the adopted child of a preacher, church features prominently in her therapy and she is in that way afforded an understanding of right and wrong, even if it comes from fairy tales. She is seen feeding farm animals and holding hands with adults. She gets the childhood she deserves, the one that was forcibly taken from her—even if it comes at the tail end of a 30 minute pearl-clutch-a-thon about her public masturbation and attempts to murder her brother.

It's almost as if humanity is a mutually reciprocated condition and that we can only expect people to be humane when we are humane to them.

(I'm not saying Beth's parents weren't kind and generous to her, and I sincerely hope that this film does not sway any of you from considering adoption. Rather, consider: To what end do we delay the recovery and rehabilitation of trauma survivors by sensationalizing the symptoms of their pain?)

Beth Thomas is now a nurse in Flagstaff, Arizona. She works in neonatal care, helping to provide, in some way, a safe and caring environment for vulnerable children. She was a proponent of Attachment Therapy for a while—she holds the distinction of being the only adult survivor of Attachment Therapy to speak well of it. Just to give you an idea of the emotional tolls on the therapy required to become "a part of society" post-abuse.

I like to imagine this as someone who was hurt using their experience and compassion to help aid those in need, to shield and protect them. This gives me hope that my abuse, and that inflicted upon those close to me, does not define and confine us to liabilities of polite society.

Beth Thomas may not identity with that narrative precisely, but we'd agree that it's an improvement on "beware the girl who cannot love."

Don't fear the diminished empathy—it just might save your life or check your newborn baby's vitals someday.