In an essay on lesbian life in the '50s, Joan Nestle recalls a mafia-owned New York bar called the Sea Colony that posted a guard at the bathroom to hand out the allotted amount of toilet paper and to enforce a one-occupant-at-a-time policy—despite the bathroom holding several stalls. As any woman with a bladder knows, the result was an endless line: a perpetual queue that wound around the bar. And as Nestle tells it, a line act developed in that spiral of queer bodies—a joking, cruising, strutting, preening, boldly creative acting-out of proud butch and femme styles. According to Nestle: "We wove our freedoms, our culture, around their obstacles of hatred."

That bathroom line is a perfect metaphor for the way we see, over and over again, especially throughout queer history, that oppression and resistance are inextricably interwoven. Even in the harshest conditions—perhaps especially in the harshest conditions—individuals and communities find ways to connect, resist, celebrate themselves, and create rich and enduring alternative cultures. The lesbian and gay taverns that claimed social space for queers in the 1950s laid the foundation for the LGBT communities and organizations that developed in the '60s, '70s, '80s, and beyond. Nestle notes that every time she took the fistful of toilet paper, she swore eventual liberation: "It would be, however, liberation with a memory."

My noir mystery, Blackmail, My Love, is dedicated to keeping that memory alive in all its pain and glory—and with it the knowledge that for many queers, in the U.S. and throughout the world, those days aren't over. My graduate research at Yale involved interviewing older lesbians about their lives in the '40s, '50s, and '60s. Their stories have haunted me since. These stories, along with those of gay men, bisexuals, and transgender people shared by friends, are woven throughout the novel. Many of these tales are tragic, but they also include dazzlingly creative acts of resistance, and the particular thrill of connection charged with danger.

Blackmail, My Love follows Josie O'Conner as she stumbles off a Greyhound bus in downtown San Francisco in 1951. She's come to find her gay brother, Jimmy, who'd been working as a cop but was thrown off the force under murky circumstances. He became a private dick and was investigating a blackmail ring targeting queers when he disappeared. Josie adopts Jimmy's trousers and wingtips as well as his investigation: Josie becomes Joe, then sometimes returns as Josie. This gender-flexibility enables the character to move stealthily between the demimonde of the queer underground and the upper crust of society, in a sense using society's gender rigidity as sword and shield.

Joe suspects that two groups may be involved in Jimmy's disappearance, the blackmailers or the cops—or both. The blackmail victims run the gamut from a timid, shame-ridden schoolteacher to a brazen butch who spent the years between the wars as a tuxedo-clad trumpet player in Paris. In some ways, that's what I most wanted to explore in this novel: what was it like for our queer ancestors who believed everything they said about us in the 1950s, and how it was possible that some of them managed to believe none of it? What generally made that possible: community.

Community formation was the pivotal piece of work LGBT people accomplished in mid-century America. More and more of us found each other, formed friendships and networks of friendships, established bars and cafes and even neighborhoods, and began to say: Here we are. In an era that, for the most part, understood homosexuality as a psychiatric illness afflicting isolated individuals, this was a bold step indeed. Bars like the Sea Colony, and San Francisco's legendary Black Cat Café, played a critical role in the process.

There were other ways we found each other, though, and the codes could be subtle. Consider how Joe finds assistance—of many kinds—in an unlikely place: Police Headquarters.

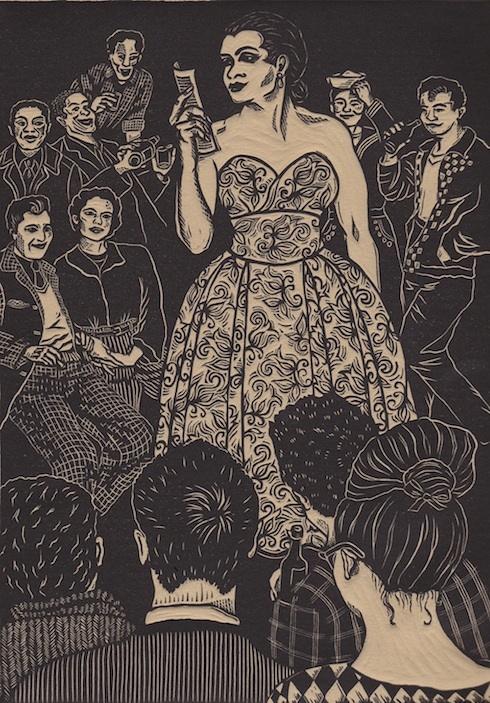

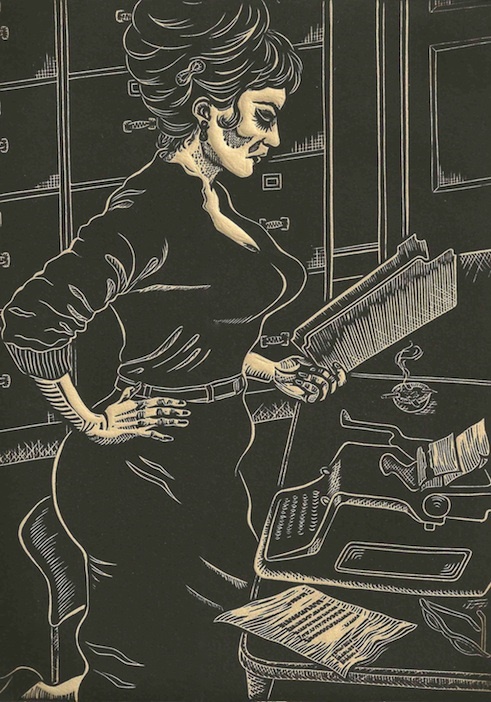

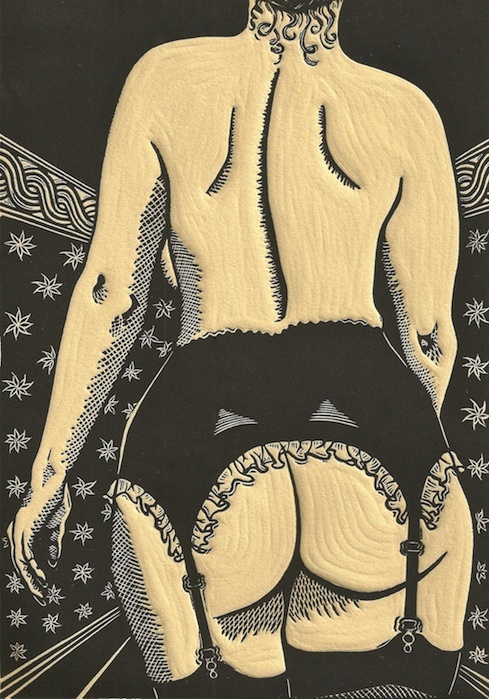

The door said "Personnel." I pushed it open and there she was. Crimson bouffant towering to improbable proportions, green peepers enhanced with enough eyeliner to stripe the 101 from here to Los Angeles, cavernous cleavage, hips generous as a cherry tree in June, and a derriere that defied gravity. She looked up from her typing, gave me a good once-over, then tilted her head to take another gander over her rhinestone-encrusted cat eyes. She raised her right eyebrow inquiringly . . .

"I need your help," I said quietly.

"I'll bet you do," she agreed, in a voice that leached whiskey and cigarettes. She slid the drawer shut with a thrust of her hips and sailed majestically toward the desk. Her breasts preceded her like the prow of a ship. I wondered how that ass could be so high and firm without cantilevering. Settling it in a chair that was surely the envy of most cops in the city and a good number of the robbers, she indicated another. I sat. She began drumming her fingers on the desk.

"My brother worked here. Then he didn't. Then he disappeared."

She nodded.

"His name is James O'Conner. He goes by Jimmy."

She nodded again, more slowly. "What do you need to know?"

"Who was in that brawl with him, the one that got him kicked off the force? And when did he stop working for the police?" She looked doubtful but sailed back over to the cabinets, pulled a file, flipped through it, and piloted back. I wondered how many idle questions she got in a week from people who just wanted to admire her ass while she looked for the answers.

"His employment was terminated on April thirtieth." She lowered her voice. "There's nothing here about the fight. Disciplinary files are kept in Sergeant Wiener's office."

"There must have been some talk when it happened."

She was drumming her fingernails again. "I wasn't privy to the details."

I stared at her hand making that rhythmic sound on the desk. Her fingers were long and plump, her nails crimson, just a shade or two away from her hair. Two of those nails were shorter than the others. The last two in that drumming line. Distinctly shorter, filed back below the tip of the finger. I looked up. Her green eyes met mine, followed my gaze to her fingernails, then traveled back to my face.

"I need to find him. Please, can you help me?" I whispered. She glanced in either direction and picked up a pen. Her plump fingers scribbled on an envelope and slid it across the desk. Just then a door to the right opened, a hand appeared, and a voice commanded "Miss Locket, the file of Officer Michael Miller."

"Right away, sir." She turned to me and said crisply, "Glad I've been of assistance." Then she soared back to her filing cabinets.

"Right away, sir." She turned to me and said crisply, "Glad I've been of assistance." Then she soared back to her filing cabinets.

I left clutching the envelope. Outside the building, I uncrumpled it: "Black Cat, 6:00. Lucille."

At the Black Cat Café—a "bohemian" bar frequented by beat poets, prostitutes, longshoremen, and Queers—Joe encounters the legendary drag queen José Sarria and witnesses the Black Cat's version of the Sea Colony's bathroom. San Francisco's finest stroll in to collect the money they routinely extracted from Queer bars in exchange for the promise of protection from raids (which they only sometimes delivered). The bar's clientele settles the score, engaging in one of the many humble, everyday acts of resistance that buoyed hearts, built camaraderie, and nourished courage in the Dark Ages of Queerdom:

Lights flickered, the room froze. I poised to sprint toward what I hoped would be a back door, but nobody moved. Two policemen swaggered in, sneering. One was tall, the other taller, and both walked like they owned the place. Their belts, oversized charm bracelets, dangled nightsticks, handcuffs, and holsters. As they strolled to the bar, those on the first few stools decamped hastily. The bartender pulled an envelope from under the cash register. The tall cop slid it into his breast pocket, then ordered two beers. The taller cop pointed to a spot high on the wall and said loudly, "Our glasses." The bartender reached for two tumblers set apart on the top shelf and poured their drinks. The room was subdued and tense while they drank. Then they swaggered out like they'd swaggered in. The entire place exhaled as the bartender bellowed, "Time to wash 'our glasses,'" and a stampede ensued. By the time I reached the alley a crowd circled the two tumblers. I peered between shoulders. Six men, flies unzipped, peed into the glasses as urine spilled over like frothy champagne.