In the water, penguins are all grace and power, but "on dry land what do you got? Just a wee prick." So says one of the stubbly old salts early on in Black Sea, providing a nice thumbnail summary of the film's phallic obsessions. This is a movie about manly, working class men getting castrated, over and over—on land (like those penguins) and even, alas, under the sea. And while manhood is at stake in just about every action movie, Black Sea is particularly pointed in its focus on the way that working class masculinity is threatened, and how those threats lead to violence and death. Those penguins may be graceful, and they may be ridiculous, but in this film, they are also ridiculously, gracefully grim.

Political scientist Adam Jones has pointed out that men suffer 93% of occupational fatalities in the U.S. As this film suggests, it is overwhelmingly men who go down in subs, or out on rigs, or into coal mines, and are killed in the name of duty or money. Black Sea seems to push back against that reality—to express the rage and pain of men who are seen as disposable, worthless, and fucked. But the only way the film can sympathize with them in the end is to reimagine discarded lives as self-conscious sacrifice.

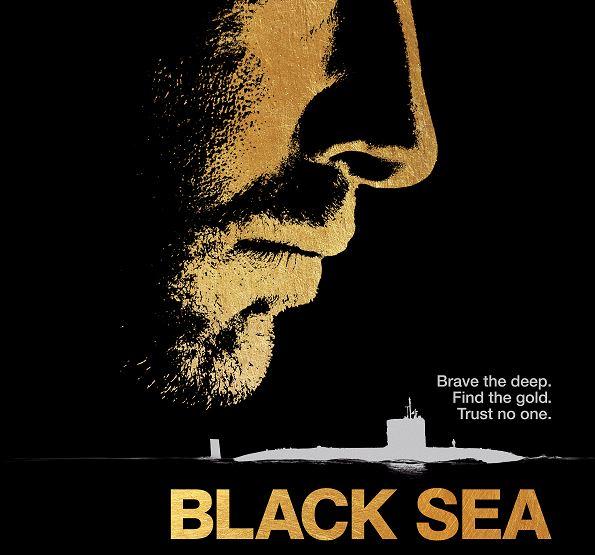

The film opens with submarine captain Robinson (Jude Law) being fired from his job at a marine salvage company. His plight is hardly unique though; the film is filled with (mostly bearded) men who are cast-off, abandoned, and impotent. De-industrialization and depression have left men without work, and so, the film suggests, without manliness. One former salvage worker has a paper route; Robinson himself goes to the employment office and is told to flip burgers. The men have little else to fall back on . . . other than a different manifestation of employment and thus, their masculinity.

"I lost my family to this job," Robinson rages, but his family hardly exists in the film; a few glimpses of his wife and son from a distance and some flashbacks are all the screen time they get. One other character, the 18-year-old Tobin (Bobby Schofield), has a pregnant girlfriend; we almost see her on his iPhone. One other character has two daughters. Otherwise, there's little mention of family.

Men are their jobs; there is nothing else.

And in this case? Robinson's job is extremely dangerous. After the firing, a friend tells him about a sunken Russian sub in the Black Sea with tens of millions in gold bullion. Because of territorial disputes, no one has been able to salvage it. Robinson connects with an investor—who meets him insouciantly in his pajamas—who wants the crew to take along his sniveling flunky Daniels (Scoot McNairy) in order to keep an eye on things. Daniels then stands in on ship for all the wealthy bankers and investors who control the world up above— including the wealthy man Robinson's ex-wife married. Robinson resents him, and Daniels, and all of the powerful, collectively referred to with the all-purpose homophobic appellation "poofs."

The casual but insistent homophobia is consistently powered by the generalized fear of not being manly enough. Tobin gets nicknamed "Virgin," because he's young and clean-shaven—he's fathered a child, but then, so has the "poof" Daniels; merely having sex doesn't prove you're a man. Instead, you have to prove, more globally, that you're the one who screws, rather than the one who gets screwed over. The guys in the boat don't want to live the rest of their lives "crawling on their bellies" — they want to be men. Wealth, they hope, will give them that power.

And so they prance and preen down there under the sea for each other, trying to show who's bigger, who's tougher, and who's the one on top. The father-son affection between Robinson and Tobin is just about okay, but all that homophobia closes off a lot of possible affection or closeness—the film's male-male relationships bend inexorably towards paranoia, not solidarity. The conflicts are framed as being about greed—every man gets the same share of the gold, so offing each other is a way to increase your fortune. But when it comes down to it, the violence isn't set off by avarice, but by wounded pride. Robinson tells off Fraser (Ben Mendelsohn), and, after some nervous brooding, Fraser picks a fight and stabs a shipmate. Robinson calls him a psychopath, but the psychopathy takes a familiar form; he feels small or scared, and he lashes out. Like everyone on board, he wants to be a man; he's just more directly violent about it than the rest of the crew.

The irony, though, is that it's not the psychopaths of the world who give it hardest, but those loathed effeminate bankers and desk jockeys. The rich guys out there, on the surface, are on top. "I'll kill you poofs every one!" Robinson yells after a final betrayal, but it's an empty threat. The guys on the bottom are always on the bottom—and if they ever get on the top, then they're "poofs" too. Robinson rants about "they" and what "they" have done to him, but as one of his few surviving crew-members yells back, "Who is this they! You're as bad as them!" Masculinity—like the sub itself—is a narrow trap. You can be the castrated man on the bottom or the poof on top, the crushed penguin-worm or the dishonorable, wriggling thing that does the crushing. There's no other option—no escape suit.

Except perhaps for one. The film ends as a quiet paean to that old, heroic, gallant, self-abnegating masculinity—the cool movie star smoking a cigarette as he stoically sacrifices himself for those he loves, or those who, more narrowly, he is responsible for. To be a man, the film seems to conclude, is to put aside the agonized struggle for dominance, and accept one's identity as a sacrificial protector and provider. You give your life to your job to earn a living for your family; you give your life to protect those like son-substitute Tobin who depend on you. That's what men, and heroes, do.

The film presents that heroic masculinity with a good dollop of self-pity, but also with love and reverence. It's hard to deny the appeal of the masculine ideal, especially when embodied in such a scruffily attractive package as Jude Law. And yet, it's also a depressing vision. Is this really the only way we can value men, or that men can value themselves? To be a man, you have to drop to the bottom of the sea, or lay your life down on the field of battle?

Heroism becomes just another way to say that the only good man is a dead one.