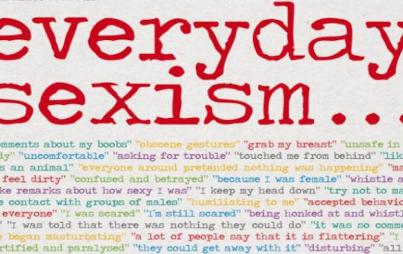

Everyday Sexism is our first Book Club pick.

“We can’t be silenced when we’re all saying the same thing...”

When Laura Bates started the Everyday Sexism Project in 2012, she had a clear goal in mind: “I thought if I could somehow bring together all those women’s stories in one place, testifying to the sheer scale and breadth of the problem, then perhaps people would be convinced that there was, in fact, a problem to be solved.”

One of the consequences of sexism being so normalized in Western culture is that many people, women included, have a hard time recognizing 1) what it is, and 2) why it’s (still) a crisis.

Patriarchy benefits from this normalization, often managing to silence even its victims by building a sense of internalized sexism which makes women minimize, doubt, accept, and even blame themselves for others’ objectification, sexualization, and/or assault of them.

Bates wanted to break this perpetuating cycle of silence by offering a platform for women to share their stories, to show that no one is alone in their experience of sexism, and that, collectively, our voices can no longer be ignored or shamed into silence.

In 2014, she organized what she had learned from the stories of over 100,000 people submitting their experiences with sexism to her project, as well as her interviews with women and insights gained from speaking engagements at schools and universities across the United Kingdom, and wrote a book of the same title.

“One of the clearest messages to emerge from the Everyday Sexism Project,” she says in the book, “has been that everything is connected…[T]he attitudes and ideas that underlie one [act of sexism] allow the other to flourish. …[T]he culture created and sustained by each incident is part of the fertile ground from which the others spring.” She concluded that it is necessary to “challenge all forms of gender imbalance and prejudice, no matter how small, in order to tackle the overall problem…”

One of the book’s early chapters, “Girls,” shows how deeply we have failed our youth, often without even realizing it. From a very young age, well before they could possibly understand what’s happening, our culture bombards girls with gendered messages about how they should act and dress, what they should like and want for themselves, and what goals and behaviors are appropriate for them. These messages, ingrained in adults since their childhoods, are often reinforced by parents and other adults in these children’s lives.

Boys receive problematic gendered messages as well, but girls are taught to politely and quietly accept the place that has been made for them in society, while boys are allowed much more freedom to explore, reject, and influence their own paths. As Bates explains, “[G]irls are socialized into submission and into acceptance of others’ behavior — even when it invades their personal space. But nobody had ever taught her that she had the right not to be touched without her consent.”

Even before girls enter puberty, our culture has already begun to sexualize them. Yet, as girls get older and begin to explore and express their sexuality, they quickly find themselves balancing on a sharp, double-edged sword. “[A]fter they’ve been sexualized and hounded and harassed and bombarded from pretty much every angle with the notion that they are sexual objects, there to be sexualized and fantasized about and pursued, then they get ripped to shreds for being too sexy…”

There’s no way for them to win. They are utterly unprepared to deal with a society that is constantly sending them mixed messages, yet every day they face the very real and serious consequences of living in a patriarchy which discourages their protest. Listen to these words from a few young women about sexual harassment and assault, featured in the book.

“I had no idea how to react. So I waited it out.”

“Having always been taught to be polite and not make a fuss, I was totally unprepared.”

“None of the girls I know would describe any of this as sexual harassment. It’s just ‘boys being boys.’”

“Girls walking with their chin up gives the wrong impression.”

THESE are the lessons that girls are learning from our society. Whatever we tell ourselves about how we are teaching our girls that they can “be whoever they want to be,” that is not the message that is getting through. Whatever girl-positive messages we may think we’re putting out there, what’s sinking in is that girls can expect to be harassed without any expectation of how to fight back — or even that they can.

One common refrain that’s made against accusations of sexism is that things as “minor” as gender-segregated toy aisles and complimentary catcalls are ultimately harmless. But there’s nothing “harmless” about the thousand little things that add up to women and girls conditioned into accepting fear and shame as part of their daily routine of walking home from school or having a girls night out. We tell them that being groped or shouted at is minor, nothing to get worked up about, but listen to this submission to Bates’ project: “It seemed minor; scared the hell out of me though. I was crying by the time I got home.” Does that sound like no big deal to you?

Another common excuse to everyday sexism is that it’s just a joke. Just humorous, light banter that no one’s supposed to be bothered by. But, as Bates asks in her book, “What kind of ‘banter’ is it when young women regularly feel routinely humiliated and terrified for speaking out against their own objectification?” For something that’s supposedly “just a joke,” it carries very real consequences.

In the chapter “Double Discrimination,” Bates talks about how women who deal with intersecting oppressions experience sexism. What I appreciated most about this chapter is that it, more than any other chapter, it allows the women who submitted their experiences to the project to speak on this subject in their own words.

The author notes within the first few paragraphs of the chapter that “though this section is designed to give these intersections between different forms of prejudice the attention they deserve, they also run throughout the other sections of this book… The inclusion of this chapter does not conveniently distance and compartmentalize its subject matter as one clean-cut area of sexism, and nor is it intended to ‘other’ those subjected to such double discrimination.” I’m not sure, however, that the author’s intention was achieved.

My biggest problem and fundamental disagreement with the author was on the chapter “What About the Men?” First, she seems to contradict herself when she posits that “some women don’t face sexism.” That’s just not true, but I think she begins to complicate things for herself by simplifying her definition of sexism, which she describes as “treating someone differently or discrimination against them because of their sex.”

This over-simplification of the definition of sexism is similar to a lot of people’s misunderstanding of racism. If we say that racism is when you treat someone differently or discriminate against them because of their race, then white people can also experience racism. However, this is an inadequate definition that does not take into account the structural and institutional power of oppressions like racism or sexism.

The idea that “some women don’t face sexism” is as ridiculous as saying “some black people don’t face racism.” Sexism and racism are both institutional oppressions. They are supported and normalized by countless aspects of our culture and taught to us in myriad large and small ways since childhood.

Describing the oppression of sexism in the chapter on intersectionality, Bates explains the effect of compounding sexist acts on women’s psyche. “Because it isn’t just about the individual incidents; it’s about the collective impact on everything else — the way you think about yourself, the way you approach public spaces and human interaction, the limits you place on your own aspirations and the things you stop yourself from doing before you even try because of bitter learned experience.” The institutional nature of sexism affects everything.

Yet Bates pushes the narrative that men experience sexism as well. While she acknowledges that the impact of that sexism is not as frequent or severe for men as it is for women, she misses the point. Sexism serves a social purpose — it maintains the patriarchy. And while patriarchy promotes toxic myths about masculinity and a binary view of gender, it supports masculinity. Men are allowed to be men (in however limited a sense) but under patriarchy, women are not allowed to be women. There may be a narrow view of what it means to be a man, but there is no way to successfully be a woman.

“[Sexism] gives us endless reminders,” says Bates, “of the vulnerability and victimization of women. It lets us know that it is normal and common for women to experience assault and harassment and rape. And it tells us that we deserve it. And all the while we are conditioned to be passive and pleasant, not make a fuss — to be ladylike and compliant and socially acceptable. Before we ever experience violence we are conditioned to expect it — and to accept it.”

THIS is sexism. Cisgender men do not experience this.

Yet Bates wants us to basically excuse the fact that men are sexist because most of the time, she says, “men’s sexist behavior is not intentional or deliberately prejudiced, but simply the result of being immersed in a very patriarchal culture.” To me, this is similar to suggesting that it’s not really someone’s fault if they’re racist because we also live in a very racist culture. That’s just not good enough.

She goes on to share a story an interviewee told her about how men are socialized to be sexist. The woman is describing a scene a former boyfriend talked to her about about locker-room banter.

“…it seemed that the worse you treated a female the louder the applause, whereas any respectful behavior or indeed any indication of liking a female as opposed to just using her body as a means to an end was met with ridicule. […] There was a big emphasis put on humiliation.”

These are the men she wants me to sympathize with? I guess I’m not as willing to excuse men, individually or as a gender, when they refuse to question or challenge sexism just because it’s what they’ve been taught.

Bates does end the book on a positive note, though. She talks about the empowerment that comes with knowing that you don’t stand alone. In and through our shared stories, we find strength in each other and the realization that we are strong enough to fight back and win. “We can’t be silenced when we’re all saying the same thing,” she says. And I do agree with her on that, definitely.

Questions For Our Discussion:

Which chapter(s) in the book did you most identify with?

Did reading the book expand your understanding of sexism? What, if anything, about the stories shared in the book surprised you?

Was there anything in the book that you disagreed with or were disappointed by?

How can feminism help challenge and change the narrative about sexism?