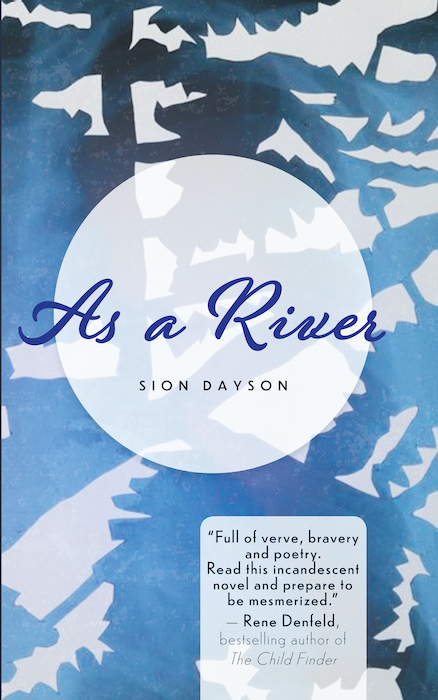

As A River by Sion Dayson

Ravishly is thrilled to share an excerpt from Sion Dayson's As a River (September 2019, Jaded Ibis Press)

It’s 1977. Bannen, Georgia, nestled amid pine forests, is rife with contrasts: natural beauty and racial tension, small-town charm and long-term poverty. An unsettling place for a Black man who fled it years ago and has since traveled the world.

But Greer Michaels has to come home, to care for his dying mother. And that means he’ll have to reckon with the devastating secret that drove him out in the first place.

Greer’s story is intertwined with those of the people around him: His mother, Elizabeth, who once had a dazzling singing voice but fell silent years ago. Their neighbor Esse, who has turned to religion after her own traumatic past. Esse’s teenaged daughter, Ceiley, an insatiable reader with a burning curiosity about life beyond Bannen’s town limits.

Written in spare and lyrical prose, As a River moves back and forth across decades, evoking the mysterious play of memory as it touches upon shame and redemption, despair and connection. An exploration of family secrets rooted in the turbulent history of the segregated South, As a River is ultimately about our struggles to understand each other, and the stories we tell ourselves in order to survive.

Chapter 1 excerpt from As a River

Ceiley grew up hearing of her own immaculate conception. Kids in the schoolyard would ask her who her father was, goading her to say God. She never did, but that didn’t stop their taunts. Stories thick as kudzu in that town. Everyone knew about her mother.

The town, Bannen, was a small one in middle Georgia, made of dirt roads and modest homes; the air heavy, ground loamy. Oak trees and chickenfeed, the Cherokee Rose that offered a second flowering in the fall if lucky; these were things you saw from the front steps of Wilson’s General. People said they could smell Sicama River, better known as Snake Creek, from half a mile away—about as far as anyone ever went. On warm summer evenings, a remote train whistle would sound, a reminder of other places in the distance. But mainly, like the train’s call, a town beyond Bannen was a reality fleeting, then gone.

Ceiley hadn’t heard the whistle, was still sitting at the dinner table, moving the lima beans across her plate into pleasing geometric patterns. Trapezoids, hexagons, equilateral triangles. Her mother clanged dishes behind her, as if a chorus could be made of pots and pans. When the tap stopped running, one final gurgling sound issuing from the drain, Ceiley heard Esse’s familiar huff. She didn’t need to turn around to know her mother was looking critically at the back of her head, finding fault with her unraveling cornrows, or the unsatisfactory way she slumped her shoulders. Ceiley ignored these silent assessments and waited for Esse to move to the closet for the broom.

“Mama,” she said, “Sheila asked me to come over to her house after school tomorrow.”

“Who’s Sheila?” Esse asked, starting to sweep near the stove.

“Someone in my class. You know, one of Mrs. Stevens’. She’s nice. It would be nice to go. She lives over on Cedar.” A vegetal rhombus, perpendicular lines intersecting.

“You know we have plans.”

“Mama, really,” Ceiley said, “do I have to go to church with you every day?”

“Child, what kind of question is that? The Lord is with us every day. He always shows up.”

Ceiley shifted her beans into straight lines, the flanks of a regiment. “Mama,” she would try to put it in her mother’s language, “I’ve already prayed for everything—peace, love, health, humility. Not much more to do.”

“Humility?” Esse said, the broom’s rapid scratches on the worn linoleum floor coming to a halt. “Girl, you like looking up words in that big dictionary of yours, I think you need to look that one up again. You prayed for every living being already? There are more creatures on this earth than days you’ll be alive, you could start with that.”

Ceiley dropped her fork on the plate, the bang louder than she expected.

“Damn it, Mama, I’m fifteen. You never let me do anything,” she said, the words flying from her mouth before she could stop them.

“There will be no swearing in this house,” Esse said, coming toward her, gripping the broom’s handle so tight Ceiley imagined splinters of wood suddenly shooting forth from her mother’s fisted hand.

“Nothing’s allowed in this house!” she said, pushing her chair away. She ran out the back door and circled around the small house, muttering what her mother would consider further indecencies. In her agitated state, she collided with a man on a bicycle.

“Are you all right?” the man asked, jumping off, laying the bike on its side. He reached a hand out to Ceiley, who was splayed on the ground, and helped lift her up. Ceiley dusted her clothes off, dazed, unable to meet the man’s eye.

Seeing that she was fine, the man laughed. “Kid, maybe you should look up, see where you’re going.”

The front door flung open. “Girl, don’t think you can run out like that,” Esse shouted. She looked liable to say a lot more, but seeing the man standing there stopped her short. She looked at him for a few long moments, then nodded slightly, as if she had just decided something in her head. “Greer?”

“Is that you, Esse? Been a long time.”

She nodded again. “Didn’t know you were back.”

Ceiley looked at her mother in wonder, speaking to a stranger like he wasn’t.

“Yeah, just got in. Came to check on my mother. How has she seemed to you?”

“She don’t get out of the house, can’t say that I seen her much.”

“Of course,” he said, as if this were helpful information. Then, after a pause, “and how are you?”

Ceiley could see he was looking at her mom, squinting a little which made tiny lines appear by the sides of his eyes, but for one exquisite moment her own breath caught imagining that he was asking her.

Beautiful.

Now that she allowed herself to study him, she took in just how beautiful he was—soft-looking skin the color of cocoa, a wide carriage, a warm, if hesitant smile.

“Fine, just fine,” Esse was saying, waving her hand as if brushing the question away.

He nodded, then looked at Ceiley. She flushed, having those deep, kind eyes trained on her, something flickering behind them.

Before she could figure out what, her mom went and ruined things as usual.

“Well,” she said, grabbing Ceiley’s arm, “we’d best be going.”

“Ok,” Greer said. “We’ll be seeing you.”

Ceiley tried to wriggle free from Esse’s grip— “Mama, I was going somewhere” —but Esse flashed her get-in-the-house gaze.

Still, Ceiley stole one last glance at the man, this Greer her mother had called him.

“Who was that, Mama?” she asked as soon as the front door clanged behind them, too curious to even fear her mother’s reprisal.

“Just a man. A man who left Bannen,” she said. Ceiley felt her mother’s look grow hot. “Don’t you get any ideas,” she said.

And what was that supposed to mean?

You Might Also Like:

-

How To Be Alone: A Q&A With Lane Moore

-

Body Language And Small Talk: Tips For Attracting New Friends

-

Shelter In Place: A Q&A With Catherine Kyle