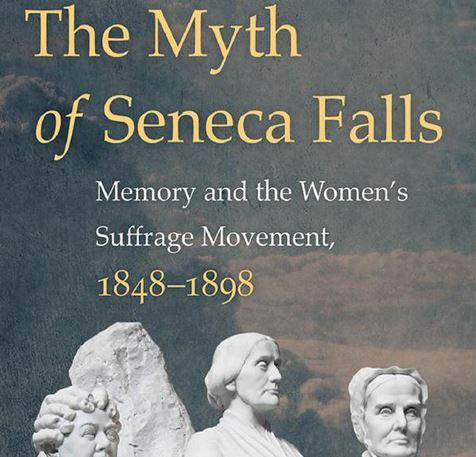

The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women's Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898

By Lisa Tetrault

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014, 296 pp., $ 34.95, hardcover

***

When Susan B. Anthony died in 1906, so many obituaries mistakenly claimed that she had been present at the 1848 Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention that the women's columns of various newspapers later issued corrections. The Myth of Seneca Falls explains why such a widespread error was almost inevitable. Lisa Tetrault's central argument is that the 1848 convention at Seneca Falls that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott helped to organize became "nineteenth century feminism's watershed event" through Stanton's and Susan B. Anthony's retroactive decision to make it that.

Their success meant that later generations of suffragists would not only come to honor Seneca Falls as the singular birthplace of woman suffrage but would assume Anthony had been there, although she and Stanton did not meet until 1851. This outcome makes clear that history differs from memory, a claim that underpins Tetrault's investigation of the provenance of the conventional 1848-to-1920, first-wave chronology.

That is, The Myth of Seneca Falls is less concerned with what happened in July 1848 than it is with how and why those events came to function as an origin story—one with long-lasting consequences for woman suffrage and women's history.

Tetrault's tale begins with the short-lived American Equal Rights Association that brought together women's rights activists and abolitionists after the Civil War. When the organization voted to support the Fifteenth Amendment in 1869—thus prioritizing black (male) suffrage over (white) woman suffrage—Stanton and Anthony decamped in outrage, and formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). Their opposition, led by Lucy Stone, formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Tetrault uses these events to set the stage for the suffrage memory battle, arguing that Stanton and Anthony wanted to ensure that women's contributions to abolitionism and the Union's victory—and the citizenship rights that they deserved as a result—would be part of the war's legacy.

In the 1870s, Stanton and Anthony began to make Seneca Falls the centerpiece of their effort to establish woman suffrage as the fundamental demand of the antebellum woman's rights movement. The 1848 meeting had formerly been viewed as simply one of many small, local gatherings preceding the first National Woman's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1850, at which Stone had been present but Stanton and Anthony, importantly, had not.

The NWSA's 1873 convention was billed as a commemoration of Seneca Falls's 25th anniversary, and it honored Lucretia Mott as a suffrage foremother. Yet Mott's letters reveal that she did not consider Seneca Falls important enough even to recall the exact year it had occurred. She also did not concur with Stanton's soon-to-be-sanctified claim that the two of them had initially discussed the need for such a meeting in 1840, when both were excluded from participating in the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Such detail is crucial to the persuasiveness of Tetrault's argument that Stanton and Anthony set out to construct a version of suffrage history that fed their goals for the movement, regardless of agreement (or lack of it) from key figures in the events they narrated. The 1873 commemoration also motivated Stanton to have the Seneca Falls proceedings reprinted and disseminated, thus beginning the process of turning the Declaration of Sentiments signed by convention participants into a "sacred text."

Such commemorative moves became a useful tool in Stanton and Anthony's struggle to rein in an increasingly chaotic postwar movement scene. Women across the country were forming grassroots groups advocating not only woman suffrage but also a variety of other causes including temperance, tax resistance, free love and social purity. Many had little interest in affiliating with the NWSA. Black women were involved in some of these efforts, but they also worked independently for improvement of the employment conditions of freedwomen and for recognition of the respectability of elite black women. Tetrault pairs her description of just how untidy women's reform politics were in the 1870s with a careful exposition of just how motivated Stanton and Anthony were to direct women's energies toward "what they believed to be the only sensible agenda: woman suffrage achieved nationally."

Their memory construction in service of this goal only heightened tensions between the suffrage movement's rival factions. In 1878, the NWSA organized the Third Decade Celebration, a much grander commemoration of Seneca Falls than the previous one. Lucy Stone declined to attend, but she would appear at a thirtieth anniversary celebration of the 1850 Worcester meeting two years later.

In 1876, Stanton and Anthony, along with Matilda Joslyn Gage, had begun to gather materials for the History of Woman Suffrage, hitting upon the strategy that would ensure their domination of public memory. Tetrault gives them ample credit for this "stunning act of historical imagination" that "created a narrative of women's history where none had existed before." This was a history with a rhetorical purpose, however. The History's early volumes not only fortified the Seneca Falls narrative, but they also forged "a new Civil War memory paradigm" in which woman suffrage was a natural outcome of the war's lesson that national citizenship entailed national protection of voting rights. Yet Stanton and Anthony's vision of universal suffrage in the History was a constrained one that "insisted that educated, white, middle-class women could, and should, speak for all women."

Tetrault vividly evokes the battles among the editors, their movement colleagues across the country who provided documents and recollections, and the AWSA leaders who refused to participate and watched in dismay as their role in suffrage history was edited out. By 1886, when the first three volumes of the History appeared, many movement activists had no memory of antebellum reform or the divisive postwar era, and the History's skewed tale began to function as the movement's "official record." The AWSA stalwarts Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell objected and tried to offer correctives, but their failure to produce a competing published account made theirs a losing battle.

When the NWSA organized the 1888 International Council of Women (ICW) to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of Seneca Falls, Stone and other detractors from the mythology of 1848 attended and made various efforts to offer a counternarrative, but they were thwarted by Anthony's control of the meeting. The ICW represented "the triumph of the memory Stanton and Anthony had been creating for the movement," writes Tetrault, and this was the context in which the movement's factions began to negotiate unification of the two suffrage organizations. Tetrault's lively narrative of the conflicts and resentments of the preceding decades makes the eventual merger seem almost miraculous. In fact, it happened in fits and starts, and old conflicts-such as state versus federal suffrage-were joined by new ones over governance, leadership, and the rules of the unification process itself.

In the end, Anthony, who fought hard for the hierarchical and highly centralized suffrage organization that would result from the merger, was the victor. Stanton was elected president of the new National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but she had never had much interest in organized politics, and Anthony, as vice president, took control of the organization and the movement. Her ascension to the presidency in 1892, and Lucy Stone's death in 1893, would cement that status. The NAWSA's 1898 convention celebrated yet another Seneca Falls anniversary—the fiftieth—and that same year saw the publication of Anthony's authorized biography as well as Stanton's autobiography, both of which shored up the myth. By the century's turn, Tetrault contends, "both Anthony and 'The Movement' were synonymous with Seneca Falls," a development aided by the NAWSA leaders' eagerness to distance the movement from Stanton, whose 1895 publication of the Woman's Bible had produced unwelcome controversy for the increasingly conservative organization.

A central contribution of Tetrault's account is its elucidation of how Anthony achieved her status as the "singular, guiding figure of women's rights." The book's Epilogue details the persistent power of the memories of Seneca Falls and "Saint Susan." After Anthony's death, the two NAWSA presidents who followed her, Anna Howard Shaw and Carrie Chapman Catt, battled over who had the greatest claim to her legacy, and Alice Paul of the National Woman's Party (NWP) would dub the Nineteenth Amendment the "Anthony Amendment." Tetrault notes the efforts of Stanton's children and Stone's daughter "to bring their mothers out of Anthony's lengthening shadow," but the myth proved intractable.

In 1920, the NWP commissioned a portrait monument of Stanton, Anthony and Mott that they had delivered to the U.S. Capitol (it was finally placed in the rotunda in 1997), and Alice Paul unveiled the Equal Rights Amendment at Seneca Falls in 1923. By that point, the NAWSA had donated the table upon which the Declaration of Sentiments had been written to the Smithsonian, where it sits today. In 1977, the National Women's Conference in Houston commenced with the carrying of a torch from Seneca Falls, and the Women's Rights National Historical Park was dedicated there in 1982.

Tetrault praises the Seneca Falls park for recognizing the importance of women's history, something for which she also praises Anthony, whom she calls "inarguably the greatest woman historian—and historian of women—in her century." Yet Anthony's success at promulgating her version of events had a price. Although The Myth of Seneca Falls is uninterested in the "truth" of when the women's rights or woman suffrage movement began—every movement has multiple origins and multiple stories about them—it does aim to establish what was gained and lost as the story of Seneca Falls took hold in the American imagination.

For example, calling the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment a "complete victory," as the sixth and final volume of the History of Woman Suffrage does, glosses over the fact that most southern black women would wait several more decades to gain the vote. Indeed, because the portrait monument featured three white women, the National Congress of Black Women objected to its move to the Capitol rotunda in the 1990s. Their activism resulted in the placement of a statue of Sojourner Truth in the Capitol in 2009, an event attended by First Lady Michelle Obama. Tetrault uses this anecdote, along with mention of Hillary Rodham Clinton's tweet about the 165th anniversary of Seneca Falls in July 2013, to bring the implications of the myth of Seneca Falls squarely into the present.

By funneling all women's activism toward a single goal, Tetrault concludes, the story told by Stanton and Anthony drastically reduced and de-radicalized what women had attempted and achieved, both in the antebellum period and later, taking a sprawling array of activities by a diverse collection of women and narrowing them down to "the achievement of suffrage by middle-class reformers." The "rigid chronology" created by the myth of Seneca Falls continues to prove difficult to challenge, and Tetrault clearly articulates the paradox created by Anthony's belief in the power of history.

She and Stanton won the memory battle and invented women's history in the process, but they left "little room to create new founding stories that might better address the challenges of the 21st century."

This story first appeared at the Wellesley Centers for Women, Women's Review of Books.

Images: Wikimedia Commons