"I think you had better call me a Man; I think you will write about me as a Man from now on and speak of me as a Man and employ me as a Man and recognize child-rearing as a Man's business

. . . until it enters your muddled, terrified, preposterous, nine-tenths-fake, loveless, papier-maché-bull-moose head that I am a man."

Perhaps the most memorable line of The Female Man is the defiant repartee following the castration set-piece.

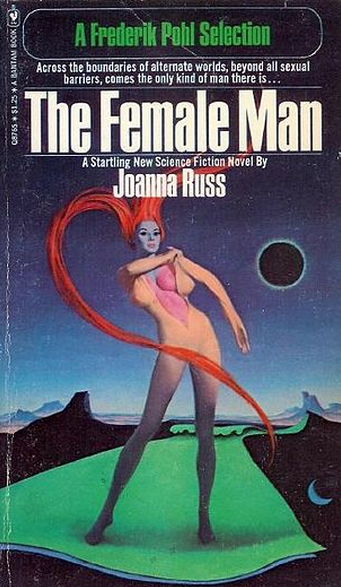

Joanna Russ' feminist sci-fi utopia, which celebrated its 40th anniversary in February of this year, is a meandering semi-stream-of-consciousness account of multiple possible worlds. In one of these alternate realities, men and women live in completely separate cultures and are engaged in a lengthy semi-cold war. As part of that conflict, Jael, an assassin, meets with an ostensibly "liberal male" who wants to bring the sexes together again.

But then this self-touted "good guy" tries to rape her. But Jael, it turns out, has Wolverine-style concealed claws, and gloriously—erotically—cuts him to pieces. ("I reached around and scoured him under the ear, letting him spray urgently into the rug.") After he is dead, dead, dead, all three of Jael's alternate selves gaze at her disapprovingly:"Look, was it necessary?" they ask.

To which Jael responds: "I don't give a damn whether it was necessary or not . . . I liked it."

However riveting, this scene is atypical of the book in some ways. The Female Man doesn't have much violence, or, for that matter, much plot. This foray into rape-revenge is about as close as it ever comes to typical genre fare.

But Jael's enthusiasm for the stereotypically "male" role of violent assassin fits neatly into the book's themes. The Female Man, as a title, doesn't mean a feminized guy—it refers instead to a woman who takes the place of a man. This refers in part to the alternate world of Whileaway, where all the men have died, and women farm, and build, and travel to alternate dimensions and take names like "Janes Evason" by which they mean, Janet, daughter of Eva.

But the Female Man is also the author, Joanna Russ herself, who appears as a character. Russ (in life and in the book) is/was a 1970s academic negotiating the university's masculine culture. She demands of her colleagues: "I think you had better call me a Man; I think you will write about me as a Man from now on and speak of me as a Man and employ me as a Man and recognize child-rearing as a Man's business . . . until it enters your muddled, terrified, preposterous, nine-tenths-fake, loveless, papier-maché-bull-moose head that I am a man."

As this suggests, Russ doesn't think much of men qua men. The joy of the book isn't just in the idea that women can take men's place, but in the certainty that women can take men's place and do it better. Jael is better at violence than the guys are—and also, for that matter, better at objectification, since her "boyfriend" is an actual biological drone/sex-object who she controls vis-a-vis a computer. Russ, as author, is similarly more swaggering than her peers—The Female Man is a high-modernist tour de force of shifting point of view and stitched-together fragments which makes virtually all its male sci-fi competitors look flaccid and dumpy.

Meanwhile over in Whileaway—the fantasy land with no men—is undeniably more virile and "manly" than our own patriarchies. Whileawayans still fight duels. Everyone there works in manual, working-class jobs. While there are marriages in Whileaway, monogamy is non-existent and everyone cheerfully hops from bed to bed. "Whileawayan psychology again refers to the distrust of the mother and the reluctance to form a tie that will engage every level of emotion, all the person, all the time." Whileawayans are filled with healthy independence. In contrast to the feminized, dependent, needy patriarchs of Joanna's world, who need constant hand-holding and reassurance, the tough, self-sufficient women of Whileaway are real men.

The Female Man is an an audacious second wave vision, which imagines a world in which the elimination of gender hierarchy leads to freedom, strength, power, and autonomy—in which, in short, the ideals patriarchy professes are actually embodied. On Whileaway, no one fears going out at night; no one cowers; no one cringes. You need to get rid of patriarchy—and perhaps of men—if you want to achieve the patriarchal ideal of free men.

So far so good. But what if the patriarchal ideal of free men is itself flawed? What if masculinity as a goal is fundamentally misguided, as some feminists (like Luce Irigaray for example) have argued?

That's not an alternate world that Russ has much interest in however. For Russ, the evil aspects of patriarchy seem to be inextricably linked to femininity. On Whileaway, romantic love is viewed as a kind of disease to be weathered and put behind one as quickly as possible. Jeannine Dadier, who lives in an alternate world where the Depression never ended, is dissatisfied and restless and hopes to find a man to make her happy. When she achieves her romance plot resolution and accepts a marriage proposal, she is filled with joy—to which Joanna Russ replies, "And there, but for the grace of God, go I."

The most explicit rejection of femininity, though, comes again in the section dealing with Jael's world, where men and women live in separate enclaves. The men still enforce patriarchy, which means they need someone to dominate—and so some men dress as and are surgically altered to perform as women. Russ' disdain and disgust at "the changed" isn't especially subtle. "The official ideology has it that women are poor substitutes for the changed," she writes. "I certainly hope so." Though the changed are of course not real, they are clearly meant as analogues for trans women; who are figured as deceived, disgusting, pitiable dupes of patriarchy.

Radical feminist transphobia was even more common in 1975 than it is now, and Russ apologized for the transphobia in her book later in her life. Still, the treatment of trans women in The Female Man can't exactly be said to be accidental. As Julia Serano has argued in Whipping Girl, hatred directed at trans women is often misogynist. It expresses a hatred of femininity, and a disgust that someone who could pass, or be taken for, a man, could instead exist in the world as a woman.

The Female Man, like much of radical second-wave feminism, is uncomfortable with those things traditionally associated with femininity—with romance, with marriage, with feminine clothes and appearance, with love and family. Whileaway is a place where women can be female without femininity—that's what Russ means when she dreams of a "female man". You can see the appeal of that dream; who doesn't want freedom, autonomy, adventure, and the chance to disembowel the occasional bad guy?

At the same time, though, Whileaway is a world that has little sympathy, and substantial contempt, for those, men or women, who are attracted to romance or love or anything else coded "feminine." In that sense, the Female Man isn't so different from the Male Man, and Whileaway—like any utopia, perhaps—is uncomfortably recognizable as our own world.

![By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons By Magicland9 [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Bell.png?itok=gWp6s_Y0)