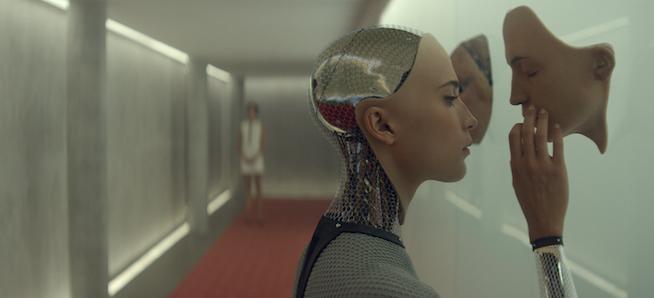

Ex Machina Promotional

The femme fatale of noir is a vision of misogyny as empowerment. In classic noir like Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep, or later entries like Basic Instinct or The Last Seduction, women are a nightmare force of corruption and violence. Their sexuality traps and destroys male innocence, as they grab hold, by the penis — the better to lead him to castration. Make no mistake that castration is greeted with fear, terror, and disgust — but also with glee. Women as supervillains allow their characters to be super powerful; a force for evil is at least a force. In a media landscape where women are often rendered secondary, invisible, and passive, the femme fatale, in her icy violence, seizes female agency along with the phallus that she so efficiently cuts off.

Ex Machina follows this blueprint to the letter. Though it's dressed up as a to-the-minute meditation on AI and consciousness, if you strip away the surface mask, the gears underneath are the familiar mechanism of noir.

Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) is a coder at a Google-like company who wins a lottery to meet the company founder, Nathan (Oscar Isaac). Traveling to Nathan's woodland retreat, Caleb learns that the genius inventor has developed a working AI, which Caleb is to question and test. The AI, Ava (Alicia Vikander), looks like a sexy, metal, semi-nude, machine/human hybrid, but in fact she's the same old femme fatale as ever. The innocent, traumatized Caleb (both of his parents died when he was 15) falls in love with her, and she ruthlessly exploits that to escape, killing the odious Nathan and imprisoning Caleb himself. The sneaky woman fucks everyone over — complete with castration/penetration imagery, as she repeatedly and wetly puts a knife into Nathan's heart.

It's easy to read Ava's violence and deception as justified. Nathan has imprisoned and enslaved her, and when he's done with her, plans to destroy her for the next level improvement—and possibly to turn her into his sex slave, as appears to be the fate of earlier AI models.

Super-rich capitalist Nathan is the patriarchy. Caleb, for all his innocence and gullibility, also (at first at least) treats Ava as a thing; an experiment — he's implicated in the system too. Destructive femininity is seen not as some sort of force of nature, but as a response to male oppression. Ex Machina is not only a noir; it's also a rape-revenge.

The revenge, though, is of a very circumscribed sort, not least because Ava is not a creation of Nathan's. She's also a creation of the film, and especially of director Alex Garland. Nathan's new-tech 3D interactive fantasy woman is, in fact, not a new-tech 3D interactive woman, but just another example of that old 2D fantasy film woman staple.

Ava tells Caleb that she hopes he is watching her at night on his view screen — and of course, it's not just Caleb who's watching her on that screen within a screen, but the filmgoer as well. We watch Ava dress up for us in ‘natural’ clothes and wig, and the pretense is the truth — Alicia Vikander, the actress, is in fact dressing up for us. Ava, the artificial woman, is really an artificial woman. The robot woman is a metaphor for the woman on screen — the film character constructed by men to deceive men (and perhaps women as well).

You could see that as implicating the viewer, I suppose: we're all participating in a system that traps women, whether in a remote cabin or in the flat image on screen. The problem, though, is that, Ava, by this logic, is not a woman. She's an image of a woman, a construct of a woman. The robot escapes her cage — but only to move to the bigger cage of the flat film screen. Ava is, after all, not a person; she is a character, and, less than a character, a trope. We learn nothing about her interiority, really; everything she says and does is a lie, a pretense, and a script. At the end we're left staring at her face as she stares at the people passing around her, wondering: What is going on in her head? And the answer is, there is nothing going on in her head. She isn't there. She's a fantasy.

Nathan wants to prove that Ava is real by getting her to turn against him. The film wants that too; Ava shows her empowerment and independence by destroying men. But that masochistic fantasy, that dream of a woman as destructive force, is still happening in a male brain.

And the surest sign of that is that the femme fatale, for all her power, is still not human. Ava is the absolutely alien, the impenetrable other. As she escapes, she registers no affect. She moves like a puppet — which she is, after all. In Ex Machina, the real machine is the intricate, clever plot, which moves the characters here and there, a virtuoso performance of mastery. The femme fatale allows men to luxuriate in the masochistic fantasy of punishment for iniquity, even as they still pull the strings. Ex Machina presents a vision of woman as free and empowered, and most of all, unreal.