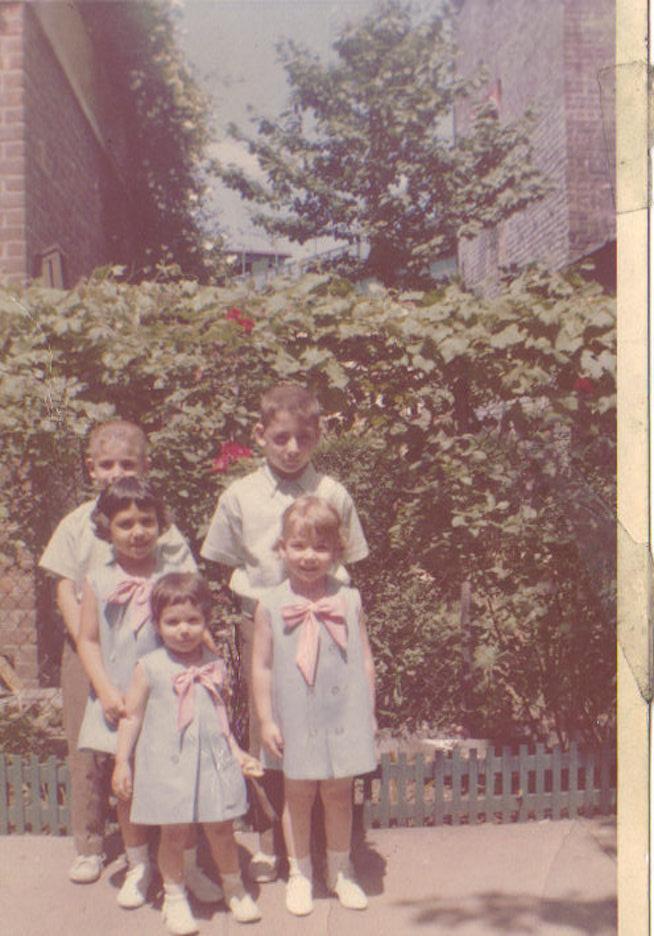

Catherine and Stephen (top left) with their fellow cousins

He underwent a smorgasbord of tests as the family anxiously awaited the answer. But we knew. The innocents in the old snapshot all knew instinctively, even before the test results came in. Stephen had AIDS.

The photograph is old and bent. We were five cousins, each born a year apart, faces bright and hopeful, wearing outfits our Nana had bought for us. We stood in a concrete Brooklyn backyard, sporting short bangs, crew cuts, and guarded smiles.

Stephen and I would grow to become closer than the others. Maybe it was our profound shyness or our wounded sensitivity — or the fact that our noses were the biggest parts of our bodies. We shared the misery of misfits that our more beautiful siblings never felt.

When most girls played with Barbie dolls, I was in love with G.I. Joe. The other boys wouldn’t even let me look at theirs, but Stephen loaned me his to explore. When my Catholic school classmates whispered about where babies came from, my mother responded with a booklet from Kotex called How Shall I Tell My Daughter?, which confused me even more. Stephen told me the truth.

As we grew older, we both became artists. Stephen drew and I wrote. To our parents’ dismay, we became freelancers at our crafts, struggling to make our respective livings but defiantly proud, commiserating with each other, always understanding the other’s plight.

I don’t remember when I figured out that Stephen was gay, but I always knew he was different. Special. Someone to be cherished. I never hung a nametag on his sexuality — it was none of my business, so there was no need to.

Then Stephen got sick. He couldn’t hold anything down, couldn’t keep anything in. He underwent a smorgasbord of tests as the family anxiously awaited the answer. But we knew. The innocents in the old snapshot all knew instinctively, even before the test results came in. Stephen had AIDS.

For the first time in our lives, Stephen and I spoke in circles. He talked about medications and treatments without actually pinpointing the problem. Even though I knew the answer, like a toddler, I finally asked, “What’s wrong with you, Stephen?” And he told me honestly, the same way he had told me where babies came from.

“How much do you know about HIV?” he began.

For the next four years, I watched as Stephen slowly died. I brought him charcoal capsules for his sensitive stomach and ginger cookies for their magical healing qualities. But whenever I gave them to him, our eyes would meet embarrassingly, as if to say, "Why bother?" But I did bother. I bothered because I loved him.

I visited Stephen in countless sterile rooms, trying to be cheerful, dutifully showing him photos of my sister’s kids, watching him smile behind his oxygen mask. What Stephen didn’t know — what no one knew — was how weak my knees grew when I pushed through the swinging doors of the ICU. I said tiny, silent prayers, begging for strength, hoping my despair wouldn’t show on my face. I would kiss Stephen softly on his forehead, the sparse hairs on his scalp brushing my cheek like the sparrow's feathers.

Once, I had the courage to blurt out, “I’m sorry.” I was sitting on the edge of his hospital bed, feet not even touching the ground. “Don’t be sorry,” he whispered. “You didn’t do this to me, Cath.”

When Stephen was out of the hospital, he didn’t pick up a paintbrush. He no longer created gentle forest creatures with human qualities or flowers pulsating with color. I knew then that we would never get to collaborate on that children’s book. I knew we would never get to do a lot of things.

The day Stephen died, I was on my way to visit him. One lung had collapsed. And then the other. My father reached me on the phone before I left. He was crying so hard he couldn’t even finish the sentence. “He’s gone, isn’t he?” I said. An important piece of my childhood had disappeared.

Stephen has been gone for over 20 years now. I still see him in many things: in the face of the nephew he never met, the boy born three months premature who we felt Stephen watched over and helped survive. The boy who is also an artist and has Stephen for a middle name.

And I see Stephen in the best parts of me.