Not all women are responding to Clinton’s message, because her vision of feminism does little to recognize the various and differing issues women face. Image: Glenn Fawcett/Wikipedia.

The candidate uses the rhetoric, but not the substance, to her benefit.

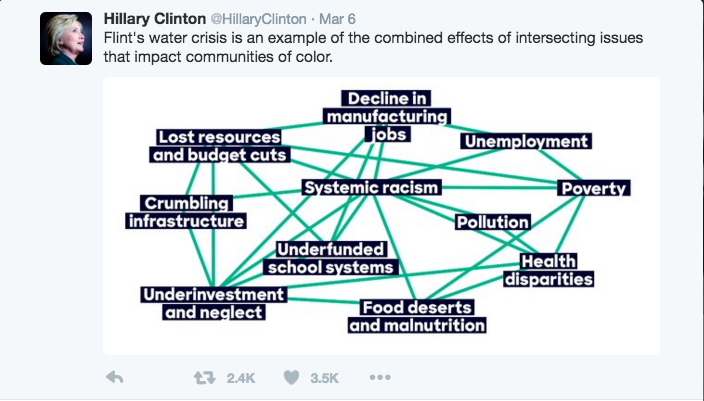

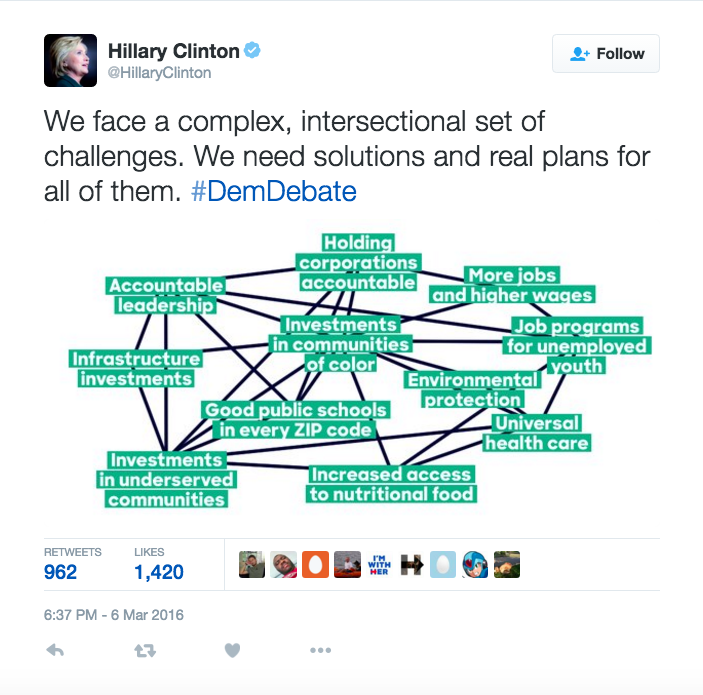

“Flint's water crisis is an example of the combined effects of intersecting issues that impact communities of color,” Hillary Clinton recently tweeted. She followed that up with a tweet that read, “We face a complex, intersectional set of challenges. We need solutions and real plans for all of them.”

Both messages were accompanied by diagrams that laid out a collection of problems such as “poverty,” “systemic racism” and “underfunded school systems,” with lines connecting them to each other, a visual way of conveying how these issues are inextricably linked. This was Clinton making an overt nod to intersectionality, a key tenet of feminism today. It was a clear effort to reach out to the young women who’ve embraced the idea—however much more in theory than in practice—whose support she has struggled to gain.

Without intersectionality, feminism doesn’t exist. At least, not if feminism is about equality and empowerment for all, and not just some women.

So what, exactly, is intersectionality, a term that has appeared in a growing number of places over the last few years? The word was coined in 1989 by African-American legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw to illuminate how social justice movements neglected black women’s issues and struggles. Mainstream feminism took a highly problematic, colorblind approach to addressing gender inequality that ignored the lived experiences and multiple oppressions faced by African-American women. Anti-racism activism did far too little to recognize and address sexism. Crenshaw describes a 1976 case brought by a group of black women against General Motors which highlighted how anti-discrimination movements failed to confront the intersecting concerns of African-American women:

Blacks did one set of jobs and whites did another. According to the plaintiffs’ experiences, women were welcome to apply for some jobs, while only men were suitable for others. This was of course a problem in and of itself, but for black women the consequences were compounded. You see, the black jobs were men’s jobs, and the women’s jobs were only for whites. Thus, while a black applicant might get hired to work on the floor of the factory if he were male; if she were a black female she would not be considered. Similarly, a woman might be hired as a secretary if she were white, but wouldn’t have a chance at that job if she were black. Neither the black jobs nor the women’s jobs were appropriate for black women, since they were neither male nor white. Wasn’t this clearly discrimination, even if some blacks and some women were hired?

Crenshaw’s invention of the word “intersectionality” helped concisely describe the many and varying ways women experience misogyny. It also called on women to recognize that while they may experience oppression in some ways, they may be privileged in others. For example, society conveys greater privilege upon cisgender women—the term for those whose biologically assigned sex matches their gender identity—than transgender women, heterosexual women over gay women, women without disabilities over those with them. As one writer explained on Womanist Musings:

Not only do I have cis privilege, I have Black female cis privilege. Yes, the Black community is not always a happy, happy, joy, joy place for women, but I have it easier than any Black trans woman. Daily I affirm this privilege regardless of my best intentions (which btw aren’t worth an umbrella in a hailstorm, because I have been raised in a cis supremacist state) Owning this, is part of how I dismantle my privilege. It acknowledges that cisgender Black women on their very own have a role to play in the maintenance of cis supremacy, outside that of Black men...Of course cis Black women and trans Black women have shared oppression and sexism is something we both have to negotiate, but I can guarantee you that just by the nature of my body, I have privilege and this readily becomes apparent in sections of society where I have power.

While intersectionality initially brought attention to barriers faced by black women, use of the term has since expanded to identify the numerous forms of oppression—racism, homophobia, transphobia, ableism, classism, and xenophobia, among others—that affect the lives of all women. An intersectional feminist approach recognizes that sexism and misogyny connect with other forms of discrimination, acknowledges that all forms of oppression are important, and is dedicated to genuine equality through the eradication of all oppressive systems that affect women. Intersectional feminist theory eschews the notion that womanhood suffices as a rallying point for all women, when so many women face challenges beyond sex and gender. Without intersectionality, feminism doesn’t exist. At least, not if feminism is about equality and empowerment for all, and not just some women. “There is no such thing as a single issue struggle,” wrote pioneering Second Wave black feminist Audre Lorde, “because we do not lead single issue lives.”

It is not difficult to locate the ways in which mainstream feminism ignores, dismisses, marginalizes and/or minimizes the challenges faced by women who do not fit into its narrow understanding of oppression. Mainstream feminist organizations go to bat for women political candidates, but say nothing about the Supreme Court’s dismantling of African-American voting rights; decry rape culture on predominately white college campuses but remain mum about the disproportionate number of black women and girls who are sexually assaulted; demand an end to spousal abuse but ignore police brutality.

Clinton’s call for an intersectional analysis of issues puts her in sync with a demographic—namely, young women—whose votes she needs and wants, but it rings hollow when considered alongside her other remarks

Again and again, mainstream feminists bemoan the 78 cents on the dollar white women make for every dollar paid to white men, but ignore that black, Latina and Native American women make 64, 54 and 59 cents, respectively. They applaud Miley Cyrus for proclaiming herself gender fluid while remaining oblivious to the epidemic of trans women of color murdered each year. They write books complaining about glass ceilings but disregard unemployment figures and workplace discrimination against disabled women. They compose endless think pieces about a video showing a young white women enduring hours of street harassment, but contribute nary a word about Janese Talton-Jackson, an African-American woman murdered earlier this year by a man she refused to give her phone number to. They shortsightedly pretend that Western colonialism has nothing to do with the oppression of Muslim women around the world.

Clinton’s call for an intersectional analysis of issues puts her in sync with a demographic—namely, young women—whose votes she needs and wants, but it rings hollow when considered alongside her other remarks. In February, at a campaign stop in New Hampshire, former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright introduced Clinton by declaring, “There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other.” The remark angered plenty of women for completely valid reasons, including that it was a simplistic take on feminist unity and because Albright (who once said U.S. sanctions resulting in the deaths of 500,000 Iraqi children were “worth it”) seems far less concerned about the lives of women and girls beyond our borders.

When asked about Albright's introductory comment and the backlash that had ensued, Clinton essentially blamed hypersensitivity and political correctness, stating, “Well good grief, we're getting offended by everything these days. Honest to goodness, I mean, people can't say anything without offending somebody.” She went on to praise Albright’s career and to suggest she had merely been offering a reminder that the fight for gender equality still needs to be waged. “I think it was a lighthearted but very pointed remark, which people can take however they choose,” Clinton concluded.

Perhaps right-wing voters will agree with Clinton on the first half of her remark—that outrage over Albright’s words can be chalked up to some imaginary PC culture of perpetual outrage—though it seems unlikely she’ll garner their votes, even with constant subtle and not-so-subtle glances in their direction. The more accurate assessment of how Albright gets it wrong lies in recognizing the lack of intersectional thinking in her words. Not all women are responding to Clinton’s message, because her vision of feminism does little to recognize the various and differing issues women face.

When Clinton dismisses her women critics as merely whiny, she also dismisses their concerns, and exemplifies the exact single-issue mainstream feminist thinking that many young women and intersectional feminists oppose her for in the first place. When she allows a young African-American woman peacefully challenging her on racialized remarks she delivered in the 1990s to be removed from a fundraiser so she can get “back to the issues,” she discounts the importance of those issues, which matter to a lot of women for whom racism is a feminist concern. When she mistakenly praises the Reagans for attention they notoriously withheld from the AIDS crisis, she insults LGBT feminists and their allies. When Madeleine Albright basically says that women should support a candidate because she’s a woman, that gender sits above all other issues, and Hillary Clinton echoes that sentiment, they indulge in the same lazy Second Wave feminism thinking Crenshaw was seeking to address when she created the word that summed up one of its biggest problems. This kind of corporate, feminism lite isn’t new, but thankfully, there is far wider recent recognition of how empty it is.

Intersectionality demands we do the real work of equality that mainstream feminism won’t.

Clinton's reply to Albright’s feminist detractors misses the point. Intersectional feminism isn’t divisive or touchy, it’s critical. Feminist author and speaker bell hooks, writing in Feminism Is for Everybody, points out that mainstream feminists who accused radical intersectional feminists of “being traitors by introducing race” missed the point. “Wrongly they saw us as deflecting focus away from gender. In reality, we were demanding that we look at the status of females realistically, and that realistic understanding serve as the foundation for a real feminist politic. Our intent was not to diminish the vision of sisterhood. We sought to put in place a concrete politics of solidarity that would make genuine sisterhood possible. We knew that there could no real sisterhood between white women and women of color if white women were not able to divest of white supremacy, if feminist movement were not fundamentally anti-racist.”

When a movement that purports to speak up for all women does not, in reality, speak out about the challenges most women face, it reveals itself as a movement to benefit the few at the expense of the many. By definition, it is therefore not just complicit in, but a tool of oppression. Intersectionality may seem like another trendy term in a perpetual cycle of buzzwords, but it defines an indispensable feminist idea that is dedicated to the equality of all women. What good is a feminism that only serves some women and elevates those to a higher and more important level? In the end, it contributes to further inequity.

Three decades ago, Audre Lorde asked, “What woman here is so enamoured of her own oppression that she cannot see her heel print upon another woman’s face?” The question is as relevant today as when it was posed. There’s no use for feminism that merely helps some women get a leg up by stepping on the necks of other women. Intersectionality demands we do the real work of equality that mainstream feminism won’t. If Hillary Clinton wants to speak to younger feminists with whom her message has thus far failed to resonate, this seems like a fairly simple, and moral idea to keep in mind.

This story originally appeared on AlterNet and has been republished with permission.

More from AlterNet: