Photo of the author by Sophie Davidson

The person I love works long days. By the time he gets home, I am usually brushing my teeth, getting ready to crawl into bed. Like many couples, often, the best and worst parts of our lives happen apart.

To stay connected, we have a long, ongoing Facebook chat stream. I’ll send him a note. Hours will pass, and then he’ll finally reply. It’s not ideal, but it’s a way of feeling less apart. In addition to actual sentences, we use Facebook Messenger sticker sets. Instead of typing Ok, he sends me a chicken winking and making the Okay symbol with its little yellow fingers. I laugh.

A few years ago, I would not have predicted I’d replace written language with cartoon animals.

Words are my world, my profession: I’m a novelist. I review books. I give talks. I teach. And yet, in my personal life, I’ll often choose a rabbit over a complete sentence. I ask my friends if they use stickers. Some agree. One uses an app that lets her create avatars of herself and her boyfriend. Some think stickers are childish. Others just that they’re cute. Some say they use emojis but not stickers.

There is a key difference between emojis and stickers. Emojis are decided by the Unicode Consortium. They’re cross-platform, and although they may look a little different—the code that means that you can type in a smile on your iPhone’s keyboard and have a smile show up in your Gmail or Twitter. This cross-platform reach is one of the reasons that with each edition of the emoji pack, there’s a rush of opinions. It matters to people if their skin tone is an option or their favorite foods appear. People want a visual language that represents their lives.

Stickers don’t make any such claim for universality. They’re local, short-lived, often strange, sometimes embarrassing. Emojis are universal, uniform, and static. Stickers can be designed by anyone, used by anyone, and therefore are far, far more individual. Anyone can create a sticker set for Apple’s iMessage.

Molly Young, a writer for the New York Times, and her partner Teddy Blanks did just that, using the work of Old Master painters. Molly felt that ‘At the end of the day I need something stronger than a yellow circle with a grimace if I’m going to be communicating, for example, “raw disgust” or “impending doom.”’ For Molly and Teddy, the yellow circle was childish. And Molly described her set as the ‘adult’ version of a sticker set.

‘The reason we settled on old paintings is that they provide the most extreme (and simultaneously the most subtle) indicators of human expression that we’ve ever seen. Need to communicate dread? Try Goya. Grave disillusionment? Hans Holbein. Drunken glee? Frans Hals is your dude.’

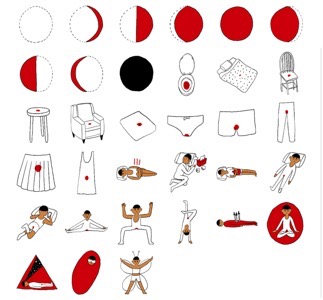

But just because you design it doesn’t mean Apple will accept your set. There are still those who, for better or for worse, decide what is acceptable to represent. Graphic novelist, comic artist, and meditation leader Yumi Sakugawa designed a sticker set that was rejected by Apple. It featured cartoony depictions of menstrual pads and tampons covered in period blood. Yumi told me that the official rejection stated that ‘depictions of menstrual blood could be potentially offensive to certain cultures.’ Yumi was disappointed writing to me that—‘I created the sticker pack to destigmatize menstruation.’ Rather than an exercise in cultural sensitivity, Yumi saw this as misogyny. ‘I mean, we have a poo emoji and a syringe full of blood emoji and guns and bombs and a devil emoji, but those are okay even though certain groups may find those images potentially offensive!’

Despite stickers not being required to be the languages we are given and the ease with which we access them do change what we say—whether it’s the Instagram crop that allows a person to show off the most beautiful part of her life or the Twitter word limit that creates punch but slices out nuance.

Emojis, stickers, and GIFs shape our language.

We have the option to draw ourselves new vocabulary. But those vocabularies are also subject to controls.

As I wonder about the future of this new language, about whether it will be able to do more than send a cute-I-love-you, I think it will depend on whether we care enough to demand a language as complex as we are.