I'm 44 and I’ve been in second grade for eight days. What about my child? Well, she’s been in second grade for eight days, too.

I've been in second grade for eight days. Let me tell you something about second grade — it’s exhausting. The chairs are small. The floor is thinly veiled cement. The rug only has 25 spots, and there are 27 kids in class— 28 including me. There is constant learning; math with cubes and counters, reading aloud, reading silently, science, more reading, writing stories — it’s relentless.

And that’s just me, what about my child?

Well, she’s been in second grade for eight days, too. She’s the reason I’m in second grade again at age 44; she is also the reason I was in kindergarten two years ago.

I have a neurodivergent child.

Her particular type of neurodivergence makes it impossible for her to even get into her classroom by herself, let alone sit, and certainly not learn. She has severe separation anxiety and a disorder called Selective Mutism which prevents her from speaking during times she is anxious or stressed. So here I am, in second grade.

And I am struggling. I am sometimes barely maintaining my sanity. I am often in tears. I am almost always exhausted.

I’m sure she’s exhausted, too. The emotional tug of war, the anxiety, the all-day suppression of emotions that aren’t safe to express at school. But at age seven, she doesn’t have a job or other kids to worry about. She doesn’t have to cook dinner or pay bills. She hasn’t even 100% learned to identify her exhaustion, which often explodes out of her in screaming tantrums. None of this is meant to minimize how difficult it is to be the person with the problem.

But it is to say — this is hard.

It’s not back-breaking work, but it is heartbreaking. Watching her panic is hard. It’s frustrating to try to navigate her resistance to everything. It’s crushing to know I can’t fix it.

Mornings often start with a refusal to get dressed, to eat, to get in the car, to get out of the car. By the time we make it to the school, we’re both already tired, and our day hasn’t even really begun. Our evenings often end with her in a complete emotional meltdown over anything — shower, bedtime, having her hair brushed. By the time she’s in bed, none of us — her, me, her father, her brother — have anything left in our emotional reserves.

I know why this happens. I understand the emotional rollercoaster she is experiencing. Both logically, and as a person with mental illness, I understand the biological, physiological, physical, and emotional demands her daily movement through life puts on her. But on the most basic level of being a human being, I am just so tired.

You Might Also Like: Why "Neurodivergent" Is The Best Term To Use For Autistic Or Special Needs Kids

I know this isn’t unlike other neurodivergent kids. I’ve reached out to other parents, or they’ve reached out to me, in solidarity, in a safe space to complain about parenting kids that are “hard.” I talk on Instagram, usually from my bed at 4 pm, about how draining every day is, about how guilty I feel to be drained.

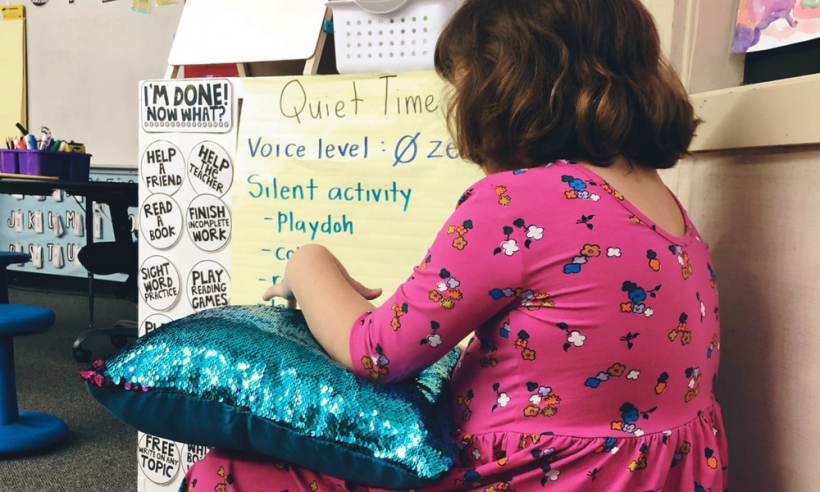

In her class, room 24, between the multipurpose room and the playground, I sit either next to or behind her, near the only window, in a beanbag chair designed for a child less than half my size. She can’t even make eye contact with her teacher long enough to take instruction, so I become the teacher. I talk her through math, counting number cubes, practicing subtraction using small, colorful buttons or erasers shaped like jungle animals — tiny tigers, smiling monkeys, colorful toucans. I help her read, sounding out words like “snarl” and “scowl.” I help her spell practicing the “th” and “ch” sounds. I gently try to push her to carpet time, from next to me, to the floor, to the edge of the carpet, and someday, hopefully, on it.

Sometimes I look out the classroom window at the Coastal Redwoods and towering fir and maple and ornamental plum trees around the playground and field like a half-circle of giant green mothers. I marvel at their beauty, their sheer size, the number of children they have watched play. I think of what it would be like if she were able to look out these windows and see the beauty, the peace, the protection of the forest around us rather than a source of anxiety.

We go to snack and then recess. I watch her sit sullenly, her eyes following the other children, unable to join in play. We file into lunch line, all 28 of us, and sit at a picnic table under a large shade structure. Meat wasps are looking for food, circling turkey sandwiches made on whole grain bread. Ella is terrified of them which only makes the entire experience more excruciating. She spends much of lunch hidden under my arm, sneaking bites of sandwich, avoiding the wasps, avoiding the gaze of her classmates who prod, “why is Ella so shy?”

In between moments of teaching, I do my job — my actual job. Or at least I try. I try to be thought-provoking, introspective, eloquent. I write articles about cleavage wrinkles. I write essays like this one. I wonder how I can continue to do this and that and everything else. Sometimes I cry. Sometimes Ella’s teacher, a kind, young blonde who wears horn-rimmed eyeglass, sees me; she must wonder why I cry so much.

At the end of the day, we walk down the stone steps on the mountainside to our minivan full of discarded grocery store ads and packaging I don’t have the energy to dispose of, which is usually parked on a narrow side street a few blocks away. I ask the children to rate their days on a scale of 1 to 10. Ella’s brother, Max, who is in first grade, says 7 or 8, depending on whether or not his classmate Clementine has pestered him in class. Ella answers 10. I review the day and my own weariness. I wonder how she can consider a day so difficult so successful; I suspect it’s just that she knows no difference. This makes me cry.

I answer 8 but think 2. I wonder when I will feel 8. It feels like I may never feel 8 again.

I know this is defeatist thinking. I know this is infinitely harder for her than it is for me. I know that I’m lucky to be able to be here with her.

What I don’t know is will she ever function like a “normal“ child? When will I be able to stand around the playground in the morning like the other moms, chatting about the things our totally average kids are doing — karate, ballet, soccer — wearing the yoga pants I put on when I rolled out of bed, coffee cup in one hand, car keys in the other? When will I leave second grade? Will I go to third grade, fourth, fifth?

I know I will keep doing this as long as she needs it because I want, more than anything to be not just a good mother, but a good mother for her, and right now this is the way I can. But that doesn’t eliminate, or even more than barely diminish the truth that I am struggling to do this, to figure it out, to go to bed every night knowing that I am going to have to to get up every day and do it again and again.

![Photo By Dr. François S. Clemmons [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](/sites/default/files/styles/profile/public/images/article/2019-06/Mr.%2520Rogers%2520%25281%2529.png?itok=LLdrwTAP)