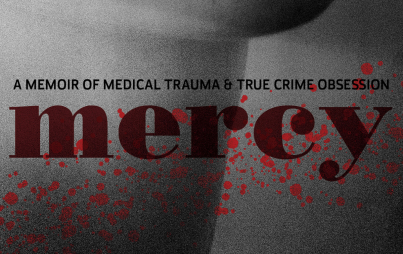

Photo by Katja Stückrath on Unsplash

This article first appeared on Luna Luna and has been republished with permission.

In the homeless shelter’s childcare center, I was the oldest child.

I was 12. My mother, brother, and I lived there for nearly a year, after having shared a room with another woman at the YMCA down the road. My adolescence was communal spaces and tiny rooms and my mother taking us to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, methadone clinics, and day-long out-patient treatments.

Looking back, the childcare volunteers at the shelter were warm and loving. I think, now, how they must have felt with a dozen traumatized children on their hands. There was the boy who stayed at the shelter after his mother was brutally beaten by his step-father. There were the twins, whose mother was pregnant and detoxing. The baby didn’t end up making it. And there was my little brother, a soft and pale child who was born into chaos and still remained loving and gentle and quiet.

Not me. I cried hysterically into strangers’ arms. I fell apart at every turn, even if I did it private. I overreacted at any noise.

A memory: One night, we watched Titanic in that childcare space. I lost it when Jack died. Not because it’s sad — because of course, it’s sad — but because I couldn’t handle loss. I couldn’t fathom the endless, giant, gaping wound that is death. Change. Lack. That we live until we don’t. That we exist until we simply fall into the sea.

Loss was a language I’d learned early but had no way to speak it out of me.

I couldn’t translate it because I was a child, and because it never ended. I’d only ever witnessed extreme poverty and countless evictions. Parents shooting up. A fatherless household. Dead grandparents. I was molested as a child. And later, I’d live in foster care, separated from my brother. My brother moved three times. I moved twice. And then the death of nearly everyone in my family. By my 30s, I would vacillate between numb and broken.

I had never known stability, safety, softness — and anytime I’d watch death, loss, or change in a film or read about it in a book, I’d have a visceral, nauseating reaction. My body was wired this way. I longed for stability, but my body had been uprooted too often.

When other kids daydreamed of crushes and cars, I was thinking of how I’d decorate a bedroom of my own. My own space, filled with books and art and things that wouldn’t be collected into garbage bags and moved from place to place.

I was both addicted to and dying from all this loss — a disease I wouldn’t realize or acknowledge until well into my 20s.

You Might Also Like: I Didn't Realize Moving Meant Packing Up My Trauma, Too

In college, I was dumped by a guy I liked. His name was Joey. And let’s be serious; he was a loser, as most college guys are.

Of course, I had cheated on him. And I’d cheated on the one before him. And the one before him. Destruction was my language, my power pattern. It made sense to dirty what I loved. It fed me. If I poison the crops, then they could never grow, and if nothing could ever grow, nothing could die. It was that simple, an ideology that would serve me until it didn’t.

But when he broke up with me, I stopped sleeping. I stopped eating. My naturally curvy body became brittle and slight. I’d go home to visit family in New Jersey, and when I’d drive, I’d have to pull over to the side of the road to cry. No, not cry — sob. I’d sob. I’d sob because the loss, any loss, was a rejection, a reminder that things end, that things go away. The breakup, which shouldn’t have affected me nearly as much as it did, pressed the “you no longer have this” trigger. Loss was my perpetual event horizon.

In a therapist’s office, I said, “No one understands the gravity of this breakup.”

But she said, “I think they do understand that it hurts you, but they don’t understand why it hurts so much, or what’s behind it.”

I instinctively knew what she was saying to me. It didn’t surprise me that the fear had followed me through the years. That my black hole of childhood was closing in on everything I engaged in. That the immensity of grief, for me, never took the form of one grief, but every single grief ever felt — all coming up to the surface, bearing its teeth and claws, during a routine college breakup. I just had no idea what to do with the immensity.

"But I just can’t stop it,” I told her. “Everything feels like I’m spiraling out, and no one will ever save me.”

One day, I stopped running from the fact that I was hurt. I needed to excavate the self. I got sick of lying to people about my childhood. I got tired of going icy when something hurt me. I got tired of not writing about the thing I needed to write the fuck about.

I wanted to know my real self, the self buried under the rubble of every single trauma and every single hyper-reaction to anything resembling pain. Who was in there? Could these two selves live together harmoniously?

Could I look back and forward at the same time?

I have had foster care dreams since the day I entered the system. From 10th grade until I graduated (a year after my peers, as I’d stayed back), I lived in strangers’ homes. I always felt dirty, ashamed, like a boarder. I’d sit with my smudged mascara and books on the floor of my bedroom when my foster mother would call down to me, “it’s time for dinner!”

It was disassociative, my body floating down the stairs, disconnected. Whose house was this? Whose life was this?

Whose sofa, whose carpets, whose food?

I lived in this disassociative state for years and carried it into adulthood. My dreams are often of being forced to go back into that home, of never feeling at home, of feeling faraway and ripped from everything stabilizing and normal.

I often dream that I’m being taken from my current apartment in New York City, as a 33-year-old, by a truancy officer, and told that I must go back into foster care. It’s just the way the system works, they’d say. And I’d have no choice. No one fights for me to stay, not even my partner.

I dream of putting my things into a single garbage bag. There’s only ever one bag. What the fuck do I bring? What do I have to let go of?

No more job. No more apartment. No more life in New York City. No more writing. I’d have to resume life as that little girl, the one who was shuttled, at the hands of adults who should have known better, between disparate realities.

Sometimes I journal about these nightmares. I sit quietly and tell myself that it’s not real right now. That I’m right here. I’m right here. And I mostly believe it.

For a long time, I didn’t realize that I was suffering from mental health issues.

I just thought I was a weird, poetic, old soul who’d been through some shit. I was just different. I was rough around the edges.

But the fact is, I live with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. For me, this presents as nightmares, flashbacks, severe disassociative episodes, extreme responses to situations, and self-destructive behavior. When I was diagnosed in my mid-20s, I refused to tell anyone, thinking I was somehow pathetic, not strong enough to move on, too sensitive to let it go. But it’s not so.

Chronic PTSD is valid. It’s the result of exposure to chronic and repetitive trauma, especially during one’s formative years. It’s the result of not having access to proper care and support. It is not about being weird, artistic, poetic, different, sensitive, not strong enough, or broken. It’s not about living as a trope or wearing a character’s mask. It’s not about romanticizing elements of the self.

In PTSD and CPTSD, our brains are literally and actually rewired by trauma.

As Beauty After Bruises says: “Complex PTSD comes in response to chronic traumatization over the course of months or, more often, years….While there are exceptional circumstances where adults develop C-PTSD, it is most often seen in those whose trauma occurred in childhood. For those who are older, being at the complete control of another person (often unable to meet their most basic needs without them), coupled with no foreseeable end in sight, can break down the psyche, the survivor's sense of self, and affect them on this deeper level. For those who go through this as children, because the brain is still developing and they're just beginning to learn who they are as an individual, understand the world around them, and build their first relationships - severe trauma interrupts the entire course of their psychologic and neurologic development.”

Today, I scroll through mantras touted by all manner of ‘love and light’ gurus on Instagram and see, “You are not your past” or “Let go of your demons,” but I am not sure I agree with either.

I am my past, and my past is me — we are the sacred twins, Luminosity and Darkness.

We are the veil, both lifted and oppressive. My demons, while they haunt me, also nourish my writing career, remind me of my empathy and resilience, and give me hope and vision. We are me. I am the demon. I am the slaughter.

None of us should have had to be resilient. And having developed greater empathy because of constant retraumatization is not exactly a fair fucking trade-off, and yet.

And I know this is the case in so many other people living with mental illness.

It wasn’t until I stopped running from the past — trying to cleanse it and scrub it and self-torture it and bloodlet it out of me — that I have come to live with it. It’s not easy, linear, or clean. It’s not that I don’t have nightmares or insomnia. It’s not that I don’t fully break down when I move houses or read about our overly-saturated foster care system or kids put into actual cages in the news. It’s not that I don’t often question my worth or my safety. It’s not that I don’t still deal with the fallout — debt, family addiction, family in and out prison. I still do deal with it. I am reminded of it every day.

But I reclaimed it now. I have made space for it to co-exist alongside my healing. I have realized it’s not one or the other.

I have spoken my trauma into the world now, and it’s no longer festering inside me.

Living with CPTSD, for me, means realizing that it’s very much a valid diagnosis, that I wasn’t at fault for it, and that sometimes the horror takes over. But now I challenge it and I challenge myself when I feel like I’m falling. I reach out for support. I treat myself with respect and patience.

But mostly it means trying to make life a little more beautiful. To rebuild and reframe and breath — even when the devil is on my back. Even when I’m triggered. Even when I don’t feel it’s possible. It’s finding a sense of harmony with the shadow, not pretending everything is okay.

I’m finally giving myself a sense of home.

~